The sun was shining. The humidity was low. It was a lovely day to pursue my keitai dreams.

Lacking a proper visa, my skies were filled with gray. Cell phone contracts are not approved for those holding temporary visitor status. Gray skies had lasted three months. Being without a keitai in Tokyo is like being without a car in Los Angeles. You feel helplessly cut off from the city passing you by. Pay phones and buses are for the birds.

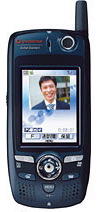

Sleek Japanese keitai are years ahead of their  American counterparts. The latest buzz is touch screens. Features like 2-megapixel video cameras with zoom, 180˚ rotating LCD screens, infrared data transmission, video call, action games, and mp3 compatibility don’t raise eyebrows. But mine did as co-workers showed off their ¥1 phones for last year’s models with technology still unavailable in the States. Phones here do everything, including the dishes…that is, if your washer is Bluetooth enabled.

American counterparts. The latest buzz is touch screens. Features like 2-megapixel video cameras with zoom, 180˚ rotating LCD screens, infrared data transmission, video call, action games, and mp3 compatibility don’t raise eyebrows. But mine did as co-workers showed off their ¥1 phones for last year’s models with technology still unavailable in the States. Phones here do everything, including the dishes…that is, if your washer is Bluetooth enabled.

During my visaless existence, a friend of a friend had lent me his old prepaid keitai. With incoming calls free, I simply bought talk time to initiate dialing – at 57 cents/minute. Calling NY was cheaper than ringing next door. The kicker was that this model was so outdated and cheap that – forget lack of camera – the operating system was only in Japanese. Beyond dialing and picking up, the functions were Greek to me.

I affixed an instructional Post-it note to the  back in the event of an emergency text message. Press the paper airplane-looking key. Select option #3. In the flashing red box, hit enter. Select #2. Scroll down to the fifth field…. It became easier not to keep in touch with anyone.

back in the event of an emergency text message. Press the paper airplane-looking key. Select option #3. In the flashing red box, hit enter. Select #2. Scroll down to the fifth field…. It became easier not to keep in touch with anyone.

However, a visa would be a passport to freely communicate using the coolest keitai, the keitai of my dreams. With the visa glue still drying, I popped into a store. I quickly realized that, despite my intention to comparative shop, I had no skills to bargain hunt.

I approached the sidewalk salesman announcing summer deals. ”Sumimasen, eigo ga hanase masu ka?” He put down his mic in mid-sentence, and handed me a bilingual phone. “No, no, no…does anyone here speak English?” Sweat dripped down his furrowed brow. The sales ladies inside were poking by the window like visitors catching a glimpse of a rare zoo animal. “Oh, no! He’s coming inside – run for your lives!” was the next thing that crossed their minds, as they went to pull straws in the back.

After failed attempts in Japanese to inquire about contracts, I found out the only English speaking au brand vendor was on the U.S. military base near Yokohama – talk about roaming. Just one operator in Tokyo was equipped to assist English speakers – a Vodafone branch in Tokyo Rail Station. There my keitai dreams were shattered.

¥1 phones only came with two-year contracts. Cancellation penalties applied. Monthly plans for one-year contracts were too expensive for my infrequent calling habits. Euphoric keitai anticipation collapsed into sad reality. To the sales clerk I uttered, “prepaid phone.”

According to Vodafone’s website, prepaid phones are ideal for people who receive more calls than they make (read: who don’t have a life – like the picture of grandpa using such a model). Since I have no friends to dial in Japan, incoming wrong number calls are free. But after three months of inconveniencing myself with an unworkable phone, I was merely swapping models. While relieved at the ability to finally set up a phone book (okay, I know three people), I kicked myself for ignorance. Since prepaid phones are not contractual, I could have purchased a bilingual model months ago without a visa.

Of Vodafone’s four prepaid models,  I, of course, eyed the cheapest. It was the same non-flip phone style as what I had. No bells or whistles. It was like asking for a IIc at the Apple store in Ginza. I refused to pocket a relic in the most technologically advanced nation. I splurged $65 for a model with a .3-megapixel zoom camera, which actually was a step up from my phone in the States. V301D only came in spark orange. So be it, at least I’ll proudly answer calls on Halloween. I couldn’t help but feel what my apartment neighbor blurted out: “You got ripped off!”

I, of course, eyed the cheapest. It was the same non-flip phone style as what I had. No bells or whistles. It was like asking for a IIc at the Apple store in Ginza. I refused to pocket a relic in the most technologically advanced nation. I splurged $65 for a model with a .3-megapixel zoom camera, which actually was a step up from my phone in the States. V301D only came in spark orange. So be it, at least I’ll proudly answer calls on Halloween. I couldn’t help but feel what my apartment neighbor blurted out: “You got ripped off!”

V301D does have a few redeemable features. Strobe light for incoming calls, sub display, and animecha. Animecha feature selectable animations that become the personality of your phone upon opening it or configuring settings. Puta the golden bear is a “cry-baby.” Hanako the bunny totes a snail on a leash. Mr. Zhen the panda “enjoys shaking his groove thing on the dance floor.” Mr. Tanimura the salaryman “faithfully does his bit at the office day-in and day-out.” Judy the white student is “as tough as one of the boys,” but “still enjoys being a girly girl.” And don’t wake Tanu-tan creature from naps, or he lashes out with bulging muscles.

All creative, but I selected Bi-nasu,  the bowing eggplant. Although nasu is one of the few foods I happen not to enjoy, Bi-nasu won me over with his lovable animations – blowing kisses, sunbathing, guzzling beer, belching, and eating his hair (the green calyx cap) [see photo, right], which also blows off in high winds.

the bowing eggplant. Although nasu is one of the few foods I happen not to enjoy, Bi-nasu won me over with his lovable animations – blowing kisses, sunbathing, guzzling beer, belching, and eating his hair (the green calyx cap) [see photo, right], which also blows off in high winds.

His bio scrolls as follows: “Generally speaking I’m impatient, but I do slow down from time to time to enjoy life in the slow lane. Whenever I have some extra change in my pocket, I like to throw back a few beers with my pals.”

Now that’s an eggplant I can relate to. Having saved more than a few ¥500 ($4.75) coins on my crappy keitai, Bi-nasu, I’m buying.

Thursday, July 28, 2005

Keitai Dreams

Posted by

ジェフリー

at

4:50 PM

1 comments

![]()

Labels: Tokyo

Monday, July 25, 2005

6.0 at 16:35

It was any lazy Saturday afternoon. Noshing on pork tonkatsu in my room, I waited for my laundry in the dryer downstairs. I was thinking about the long night ahead of me at a party I would attend in Ebisu. And then my soy sauce shook. Make that the whole building, first slowly then harder. My door was propped open, and outside I saw power lines bouncing. Jishin da (Oh, an earthquake), I muttered to myself. At least sleep wasn’t interrupted this time.

It was any lazy Saturday afternoon. Noshing on pork tonkatsu in my room, I waited for my laundry in the dryer downstairs. I was thinking about the long night ahead of me at a party I would attend in Ebisu. And then my soy sauce shook. Make that the whole building, first slowly then harder. My door was propped open, and outside I saw power lines bouncing. Jishin da (Oh, an earthquake), I muttered to myself. At least sleep wasn’t interrupted this time.

Realizing that the rumbling was only increasing, I dropped my Hello Kitty chopsticks and crouched in the entryway. It sounded like Godzilla was waking up the neighborhood. Across the alley an elderly man, jarred from an afternoon nap, stood by the window in his underclothes. Dissonant metallic groans resonated through these sleepy side streets. Buildings, bridges, and car parks were movin’ to Mother Nature’s beat. Self-reassurance that it’s going to end any moment now began to shift to how much worse was it gonna get? Before I could ponder – could it be, the long overdue “big one” – the temblors died.

Neighbors poked their heads out of doors and windows. I felt like screaming “WHOO HOO!” at the top of my lungs, as an exclamatory release to the adrenaline rush of surviving an uncontrollable act. While fortunately not the big one, this 6.0 quake was the strongest to shake up the capital in 13 years.

Tokyo is the most disaster-prone city in the world because tens of millions of people populate a dense metropolis built on an active seismic fault. Munich Re indexes San Francisco’s insured risk at 167. Tokyo’s is 710. I’m not sure what units they’re talking about, but the difference is evident.

What this means for Tokyo Tanenhaus is that while I have an emergency fanny pack handy, I’m going to insure myself with extra water, rice crackers, and cups of Häagen-Dazs. It seems that rest of Tokyo needs to wake up and stock up in the wake of Saturday’s foretaste of expected disaster.

Posted by

ジェフリー

at

9:00 AM

1 comments

![]()

Labels: Tokyo

Friday, July 22, 2005

Visa, Everywhere I Want to Be

Junk flyers clutter my mailbox. Pictures are the only clue to services advertised in Kanji lettering. This week’s offers included 80% off horses, chinchilla adoption, a dollhouse moving company, and apartments for cartoon characters. Nearly lost in the shuffle was more personal correspondence: a postcard from immigration notifying me that my visa was ready. Hallelujah!  The trip to Shinagawa immigration center in southern Tokyo required a subway to bus transfer. This bus route, however, is not exclusively for foreigners awaiting face time with bureaucrats. Local riders must dread sharing their commute with Filipinos, Australians, Chinese, Americans, and other filthy animals seeking residence permission among this xenophobic society. Curiously, a stop exists in the middle of a bridge, perhaps as a convenience for lonely leapers in a nation ranked among the top in suicide rates per capita.

The trip to Shinagawa immigration center in southern Tokyo required a subway to bus transfer. This bus route, however, is not exclusively for foreigners awaiting face time with bureaucrats. Local riders must dread sharing their commute with Filipinos, Australians, Chinese, Americans, and other filthy animals seeking residence permission among this xenophobic society. Curiously, a stop exists in the middle of a bridge, perhaps as a convenience for lonely leapers in a nation ranked among the top in suicide rates per capita.

Even Japanese obsession with order and efficiency could not streamline bureaucratic inertia. I languished in line with people from around the world to trade my postcard for a number, which then would be exchanged for the crowning glory, a work permit stamp in my passport.

I clutched 82; they were now serving 33. I began the countdown to becoming fully legal. No more crossing the street when I spotted police activity. The next number jumped to 43. Then it dropped to 27 before soaring to 75, just 7 away from the magic number. This lottery rollercoaster toyed with my emotions, especially when the blinking counter hit triple digits. Faces familiar from waiting in line had all been served. I groaned when 183 rolled around. Since leaving the country without a separate re-entry stamp invalidates my visa, I also took a number at the nearby re-entry application desk. I might as well wait in two lines at once.

“Hachi-juu ni ban,” said a man behind the counter. I remained mesmerized on the “Now Serving #146” sign. Suddenly it clicked – he was calling 82! I rushed to the counter with my ticket, thankful to at least be conversant in Japanese numbers up to 100. An enormous mole sprouted from the bridge of the man’s nose. He told me to purchase a visa revenue stamp from downstairs and to return to wait for 82 to flash on screen. These fee stamps are sold inside the convenience store on the ground floor. “One package of squid jerky and one ¥4,000 stamp, please.”

I wasn’t done with Japanese bureaucrats for the day. With work visa and re-entry stamps glued into my passport, I headed across town to my borough government office to pick up my alien identification card, which was ready after three weeks of processing. On the way inside I passed a sign for the welfare office, and considered applying for benefits. Pricey rent, exorbitant health insurance, and below minimum wage salary makes for a losing combination in the world’s most expensive city. But the feeling of having visa in hand after three months: priceless.

Posted by

ジェフリー

at

2:00 PM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: bureaucracy, Tokyo

Monday, July 18, 2005

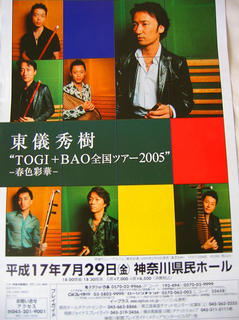

Togi & Bao

Chinese tourists I had met offered me their extra ticket to hear traditional Japanese and Chinese instruments. But for 2.5 hours? I flashed back to the painful Niijuku assembly. Ultimately, the free ticket and opportunity to hear an ancient musical art form convinced me to venture beyond Tokyo proper.

Hideki Togi is somewhat of a cult figure in these parts. About 70% of the audience was middle age to mature women. I was one of two males under 30, and the only Caucasian period. Togi moved the audience with lyrical vibrations from a hichiriki (photo, left).  He is a master of gagaku, ancient Japanese Imperial Court music introduced from China and Korea around 1150 A.D. Bao, the six-piece Chinese new-trad ensemble, also shared the stage with large red pillars evoking a Chinese setting, but in Kanagawa Prefecture. Other odd instruments included the stringed biwa (photo, lower left)

He is a master of gagaku, ancient Japanese Imperial Court music introduced from China and Korea around 1150 A.D. Bao, the six-piece Chinese new-trad ensemble, also shared the stage with large red pillars evoking a Chinese setting, but in Kanagawa Prefecture. Other odd instruments included the stringed biwa (photo, lower left)  and wooden flute-like ryuteki.

and wooden flute-like ryuteki.

Jazzy melodies lilted through the concert hall against a backtrack of synthetic beats and grooves. Modernity-infused classical court compositions. Kenny G meets the Silk Road. However you classify it, the up-tempo numbers were rather catchy.

Intermission ushered in transformation. The Shanghai Six, as I labeled “Bao,” swapped their tuxedos for Polo’s summer pastel shirt collection. Togi swaggered onto stage in bedazzled rubber pants and black cowboy boots. His white shirt sparkled from underneath a Harley Davidson jacket. Stage lights flashed. Golden hair spray shimmered. The illuminated background screen mutated ever-brighter colors. Front row fans rose from their seats and clapped along. Some waved homemade signs with shiny ribbons. Seven jesters on stage turned court traditions upside crown.

Togi commanded Papal inspiration. And like the Pope, only a select few were granted a private audience. A woman in her late 30s queued with us pass-holders. “Is this the handshaking line?” She herself was shaking at the prospect of a face-to-face encounter. Eyes wide, she twitched as if under the influence of a higher spirit.  Although denied access, she took Togi away with her in the form of a concert CD.

Although denied access, she took Togi away with her in the form of a concert CD.

Backstage, the Chinese tourists introduced me to their friends, two of the Shanghai Six (far right). Togi came over for a meet and greet. Since his English was passable, I didn’t break out my broken Japanese. And nor did I sneak off with his Harley jacket hanging nearby. When nobody was looking, I ran my fingers over the embroidery. Fingers sensed what the eyes saw, and flicked on the light bulb in my brain: Yahoo! Auctions Japan to cover next month’s rent.

Posted by

ジェフリー

at

10:15 AM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: social

Wednesday, July 13, 2005

Turn Back the Clock

Erina, Debby, Jeffrey, and Makiko all grown up

Erina, Debby, Jeffrey, and Makiko all grown up

Remember those mysterious Japanese girls at your junior high school? You didn’t get to know them. They ate those rice ball lunches and weird Japanese sweets in the corner of the cafeteria, and played volleyball after school. Maybe they only attended your school for a few years, moving away before high school, never to be heard from again. Well, at least until last Sunday.

After 11 years, I reunited with Makiko and Erina – on their Tokyo turf. Debby, my half-Japanese hometown friend, facilitated the bittersweet reunion during her visit here. Actually, I couldn't even recall their names, and swore that we had never met on account of taking classes in separate “houses” of our junior high. Makiko, however, produced a band class photo from 1992 in which she played second flute, just chairs away from this writer, then the fourth oboist. Erina tooted on the clarinet in the row behind us.

More than a decade and 7,000 miles later, four junior high graduates from 1994 shared vanilla ice cream on a sweltering afternoon. The sweet simplicity of the plain flavor complemented our innocent visages in the yearbook that Makiko dusted off. We laughed at outdated hairstyles, incompetent social studies teachers, and now deceased librarians. Coincidentally, we were the same age back then as the kids I teach now.

Let’s rewind life to 1994 to see how we appeared in our 8th grade portraits:

I think you’ll agree what a difference 11 years makes.

Posted by

ジェフリー

at

8:55 AM

3

comments

![]()

Labels: social

Friday, July 08, 2005

Khaos at Kanokita

The morning assembly ended, and lessons began. Would students live up to their infamy? (See previous post). On the third floor landing, I caught my first glimpse into a classroom through its sliding plastic doors. An airborne English textbook crash-landed on the back of a student’s head. This wasn’t going to be easy. Send in the heavy artillery. Send in the 6’2” American English teacher.

Self-introduction was planned for each class. On the blackboard I scrawled my name, birthday, nationality, and caricatures of my family. Students then asked 24 questions scripted on a printout. Based on my answers, they must have wondered if a bona fide American was in their presence. “Do you like watching tv?” No. “Do you drink coffee?” No. “Do you call to your family?” No. “Do you have any pets?” No. “Not even in America?” No.

And given rumors of their reckless behavior, I wondered if these were truly Japanese students, or just American teens in disguise. Hints of ingrained disobedience included untucked school uniforms, crumpled collars, rolled up sleeves, low-hanging slacks, desktop graffiti, misaligned desk rows, and not bowing to teachers.

A madhouse describes what I walked into for my first 8th grade class. A boy sporting typical Japanese-style bed-head and a pointy chin dotted with a distinguishing birthmark unleashed havoc with pink and red highlighters. First, he desecrated another student’s desk before jabbing the boy’s white uniform. Hoping to avoid my Brooks Brothers suit from becoming a casualty, I tensed up behind the teacher’s desk out of range, wondering how to transition to “My name is Jeffrey….” The other student returned fire, and both ended upon rolling on the floor. “Son of a bitch!” the bully cried as his victim exacted revenge. Ms. Hattori passively looked on: “The students are very badly disciplined. Don’t mind that.”

The melee ended, but the bully then perched himself on another boy’s desk before returning to his seat to cut up the handout with scripted questions, the snippets of which he dumped onto the classmate in front of him. Forty minutes later, the floor looked as if it had flurried in Tokyo in July. Meanwhile, in the rear, a group of girls pushed their desks together to while away the time writing letters in a rainbow of colors, reducing my introduction to background noise.

Seventh graders greeted me with more students on the floor. Half a dozen boys were sprawled on top of one another as if practicing a rugby maneuver. The face at the bottom was turning blue; eyes bulged from their sockets. The mass of flesh untangled itself, and the boys played JanKenPo (rocks, paper, scissors) to determine the order of the next pile-on.  For lunch, I was permitted to dine with the most mannered and inquisitive age group (photo, right). Seventh graders nibbled silently while staring at my mastery of chopsticks, perhaps waiting for me to do something foreign like ingest the salty soup of the day through my ear canal.

For lunch, I was permitted to dine with the most mannered and inquisitive age group (photo, right). Seventh graders nibbled silently while staring at my mastery of chopsticks, perhaps waiting for me to do something foreign like ingest the salty soup of the day through my ear canal.

Mischief resumed in the afternoon. An intimidating ninth grader approached me in the hallway. “Me too, me too,” he said out of the blue. “Nice to meet you. Yoroshiku,” I replied, to which he responded by dropping his pants and saying something in Japanese about his tighty-whities. Another student approached with a fruit carefully drawn on a folded piece of paper. “Strawberry,” I said with an encouraging smile, waiting for him repeat the new word. Instead, the fold opened, and the strawberry became a hairy penis. Welcome back to junior high.

I cringed walking into my last class of the day. Me too pants-dropper kid was at the board, which now read “I LIKE SEX.” He took a seat next to his friend in the front row, where together they recited an explicit line from a movie or rap lyrics. I had never heard any student curse until the earful I got today.

Hoping to change the topic, I showed them my picture album. “Bust size?” one asked, pointing to a female in a cocktail dress. “Big rack!” Me too concurred. I made it through my introduction, and had students introduce their names and favorite hobby. One agitated girl refused to answer, and soon after stormed out of the classroom, only to return a few minutes later to retrieve her bag and leave for good. The ultimate insolence.

At the end of day one, I had exhausted my repertoire of Teacher’s Emergency Japanese Phrases, including yamete stop!; shinai de kudasai please don’t do that!; urasai shut up! [lit.: loud]; and nani yatten da yo? what the hell are you doing? It’s a start, but next rotation I’m going armed with stronger language to enforce order. Anyone know the translation for, “Do that one more time, and I’ll shove my foot so far up your ass, I’ll kick your teeth to Yokohama?”

Posted by

ジェフリー

at

4:30 PM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: Kanokita

Wednesday, July 06, 2005

Bad to the Bone

History haunts Kanokita's two-tone stairwells. The sickly pale green is scuffed black while the white above has long since yellowed. Descending the stairs on our way to the Monday morning assembly, Mr. Mochizuki and I chatted candidly about the school’s past.

History haunts Kanokita's two-tone stairwells. The sickly pale green is scuffed black while the white above has long since yellowed. Descending the stairs on our way to the Monday morning assembly, Mr. Mochizuki and I chatted candidly about the school’s past.

“Maybe you have heard there are the most prolglrams at this school?” “Oh, that’s great," I said. "What kinds of programs do you have after school?” “No, no. Last year there were some accidents reported at this school. It was in the papers all over Japan.” I feigned innocence to milk juicy details.

In it’s 27 years, “Kanokita” and “success” have never appeared in the same sentence. Here, scholastic mediocrity is something to shoot for. This school consistently ranks among the worst in academic achievement in a society where middle school grades determine future salary through admission to top universities. There’s no celebration for second best, much less consolation prizes for dead last.

Although discipline and respect for authority are golden rules in Japanese society, exceptions exist. Like the crazily clad girls trolling Shibuya and Harajuku. And like the 8th and 9th grade boys at Kanokita. Mr. Mochizuki said these menaces walk out of class, eat in the hallways, and leave school property.

The school hit rock bottom in 2004 when police arrested15 students for violence. Teachers were not immune from assault, having been pelted with cans and bottles. [Apparently eating with the staff was for my own safety, lest I dine on knuckle sandwiches with students.] Miscreants wound up in a juvenile detention center. Publicity circulated island-wide. The school’s reputation sank into the gutter.

Student mutiny spooked off staff. After 2003, 12 of the school’s 24 teachers quit. Another 12 quit in the wake of 2004’s uprising, including all three English teachers, who simply stopped coming to work. The principal was given a permanent recess. With no outside applicants enticed to take the reigns of one of Tokyo’s most feared schools, the vice principal was promoted. Five years isn’t considered a long teaching tenure, but that’s the length of Kanokita's longest serving sensei. Teachers were down. Students were out – of control. The school was on the ropes.

Fast-forward: Kanokita is poised for a rebound in ’05. In 2004, shouts of “go back to where you came from” greeted new staff during their introductions. Teachers who scolded students had their collars grabbed in return. However, progress at this year’s boisterous but non-violent ceremony moved a board of ed. observer to tears.

In a gym retaining its late 70s appearance and creaking floorboards, students clamored throughout the assembly. Awards speeches were inaudible against the din without microphones. Then it was my turn. The color of my skin was ample amplification. Taking the stage, I sensed 400 pairs of eyes tracking me. Talking died down to murmurs, but that wasn’t good enough. “GOOD MORNING!” I bellowed. Heads snapped to center. Hush. “My name is Jeffrey. I am from America. I am from New York. I have been in Japan for three months. I live in Koto ward. I look forward to teaching you [sweeping gesture] English.” Mr. Mochizuki translated. The students clapped. I bowed. R-e-s-p-e-c-t.

At least for 30 seconds. Would it last the rest of the day? Find out what I was up against….to be continued….

Posted by

ジェフリー

at

11:45 AM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: Kanokita

Friday, July 01, 2005

The Losing Team

What’s it like to be on a losing team? Just ask the

What’s it like to be on a losing team? Just ask the Boston Red Sox Chicago Cubs. Or the staff at Kanokita Junior High. There are two dozen junior high schools in one of Tokyo’s quiet southeastern wards. I rotate among four. Teachers at two schools weighed in about my upcoming debut at the third. “Maybe, they are the worst,” Mr. Nakamura at Nubata School advised, wrinkling his nose. “I sink they are the worst school in all of the ward,” another teacher concurred.

“I have heard some bad things about that school,” Ms. Kimura at Douyoto commented. “Last year they got some press from students fighting. Nobody wanted to send their kids there.” Okay, clearly Kanokita wasn’t the jewel in this ward's educational crown. So, what do losers want? A sure winner. Send in the American assistant English teacher. He could turn this sinking ship around. That’s exactly what Mr. Mochizuki did. I was surprised to hear from the head English teacher in advance of my first day; no other school had called me up requesting to schedule a lesson-planning meeting.

I begrudgingly obliged. I don’t get paid enough to make goodwill visits. I paced outside of the principal’s office. The frosted glass door opened, and half a dozen ninth graders filed out. Their narrow eyes, spiky hair, and rolled up sleeves announced middle school menace. Were these the kids from the newspaper? I couldn’t imagine engaging them with funny faces and American flag pencils I hand out to reward student effort.

“The principal will now make time available to see you,” Mr. Mochizuki said, ushering me into the office. Two youthful, smartly dressed teachers joined me on the couch. They, too, were part of Kanokita's ESL team. Although Mr. Mochizuki was about 50, it was his first year at Kanokita. In fact, it was everyone’s first year here. I pondered the fate of last year’s batch of English teachers. Did they walk off the job, escaping with all limbs intact? Or might I happen upon blood-soaked clothes in a janitorial closet, or find charred femurs on the soccer field? I had been warned.

In the safety of the principal’s office, everyone wanted to know how I taught lessons at the other schools of better repute. “Well, actually I am the assistant teacher. I follow the Japanese English teacher’s lesson plan.” “Ahh, I see. So you don’t have some lesson plan of your own?” “Well, sometimes I have ideas for games.” “Ahh, do you play games at the other schools?” “Yes,” although mostly I’m a human tape recorder, I wanted to add. The teachers panned for nuggets of wisdom while the Japanese-speaking principal made himself useful at the coffee machine. Quick! How do you say, "I don’t drink coffee" in Japanese?

When I mentioned eating school lunch in the classroom, Mr. Mochizuki blanched. Ms. Hattori and Mr. Hirogashi looked at each other as if I had suggested eating one of the children – an idea equally preposterous as volunteering to eat with these troublemakers. “School permitting,” Mr. Mochizuki cleared his throat. “You will eat lunch with teachers.”

Throughout the meeting I sensed that the new staff genuinely hoped to patch the school’s battered reputation. My presence would play a key role in sparking student interest in English. Nevertheless, this was a pitched battle. Unlike Jaime Escalante in “Stand and Deliver,” try as Mr. Mochizuki might, mischievous bad apples would spoil efforts at fruitful instruction.

Will Southeastern Tokyo mimic East Los Angeles? Find out next week, only at Tokyo Tanenhaus.

Posted by

ジェフリー

at

12:40 AM

2

comments

![]()