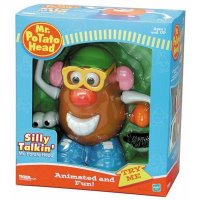

Part I here. Part II here. If Mr. Nishono were a Hasbro toy, he’d be Mr. Potato Head. None of his facial features are quite in alignment, and he’s also “silly talkin’.”

If Mr. Nishono were a Hasbro toy, he’d be Mr. Potato Head. None of his facial features are quite in alignment, and he’s also “silly talkin’.”

At first I dreaded team-teaching with him, but now I can hardly wait. It’s just so damn easy and amusing. Lesson planning occurs on the walk to class. This after a 10-minute delay where I am instructed to remain in the teacher’s room while he “prepares the lesson.”

While I wait, I comment on the day’s news to the vice principal, who is thumbing through the paper for the second time that morning. I’m not sure what else he does. I can’t read the headlines anyway, but sitting from my desk I can see the lead photograph, which is enough to get simple conversation going. Tragedy in London. Big problem for Livedoor. Angry Arabs.

Once summoned for duty, I’m briefed with an assessment of the class’ behavior, which is usually as piss poor as their English ability. Mr. Nishono wasn’t kidding about one 8th grade section being “the lowest class.” They struggled to respond to “what day is today?” and “how are you?” So I smile with encouragement, pronounce a few new words and spend the rest of class taking real-time notes of unfolding drama. The 7th graders keep my pen busy. This is the only school where the youngest are the most problematic. Even the 13-year-old devils at Kanokita aren’t this recalcitrant. Here at Omiyada School, each 7th grade class is further split into two sections. The attempt to divide and conquer has only backfired and multiplied the problem. Sort of like trying to quash insurgency in Iraq.

The 7th graders keep my pen busy. This is the only school where the youngest are the most problematic. Even the 13-year-old devils at Kanokita aren’t this recalcitrant. Here at Omiyada School, each 7th grade class is further split into two sections. The attempt to divide and conquer has only backfired and multiplied the problem. Sort of like trying to quash insurgency in Iraq.

“All teachers get nervous and shout at this class,” he cautioned me upon entering. I immediately recognized them from yesterday’s lesson when their terror level was downgraded because “the worst girl is absent.”

No such luck today.

“Hey mista, mista!!!” she screamed at Mista (Mister) Nishono as we walked through the door – quite literally. The sliding door was torn off its track, and propped up against the back wall. “Mista, I’m hungry,” she demanded. It’s two periods before lunch.

“What smell taste,” Mista muttered, resting his basket on the desk. He totes a collection of teaching materials like a homeless man’s shopping cart of recycled possessions. Teaching aids of the day were dog-eared cards of cartoon animals probably sketched by 7th graders in 1988.

Binder clips and duct tape held the plastic beach basket together. Mr. Nishono reached in for a chalk case, which wasn’t originally designed as such. “Blunt” was stenciled over a cannabis leaf on the metal cover. I’m sure it wouldn’t have taken long to find a student with a lighter.

“Let’s sing song corner,” he announced to the stereo wires he was unraveling. Mista loves to sing. If done properly, songs are valuable teaching tools. Today’s selection was “Tie a Yellow Ribbon Round the Ole Oak Tree,” which sounded like a folksy Vietnam-era tune, more recently covered by teen pop divas S Club 7 (anyone have this mp3?).

I hadn’t heard of it, even though it’s an American song and, yes, I am American. Mr. Nishono’s reaction led me to believe that I’m expected to know my nation’s entire discography (can someone please send me the S Club 7 version?).

It didn’t matter because the students, if they were conscious, yawned their way through the song. Mista hummed along. I hugged the window like a lizard trying to absorb sunlight. Hallways aren’t heated, and the missing door was turning my fingernails purple. Toes tingled with a numbness that I haven’t felt since after a full day on the slopes.

The lack of a door was also a problem for the chipmunk-looking science teacher in the adjacent class who appeared at the opening to flash a volume-reducing gesture.  The hungry girl continued to stir the pot. Mr. Nishono had enough of her insolence, and yelled at her to follow him out the door. She wouldn’t budge. Finally, she walked half way, but turned back toward her giggling friends. She wouldn’t get off scot free. Later in the day I spotted her and two boys lined up in the hallway being scolded by two teachers. It takes a village to control Omiyada 7th graders.

The hungry girl continued to stir the pot. Mr. Nishono had enough of her insolence, and yelled at her to follow him out the door. She wouldn’t budge. Finally, she walked half way, but turned back toward her giggling friends. She wouldn’t get off scot free. Later in the day I spotted her and two boys lined up in the hallway being scolded by two teachers. It takes a village to control Omiyada 7th graders.

It was then time for the guess animal game where I “please become a certain animal and students guess.” Monkey and frog went fine, but spider deteriorated into arm wrestling a boy with shaved eyebrows in the last row.

He tricked me into using my weaker left arm while he added to his advantage by pulling down with his torso to force my biceps to surrender, but not before the already loose desktop became fully unhinged. I don’t go down without a fight. I could only shoot him dirty looks while he gloated over his cheated victory over sensei.

While the bell was ringing, Mista ran out the door. “That was fast,” I said to the student sitting by the empty frame whose cartoons proved a good source of entertainment for us both during the 50-minute “lesson.”

“Baka,” he said. “Hage,” he added. Students have several monikers for Mista. “Stupid” and “bald” are the most popular. I laughed in agreement on both counts.

Friday, February 24, 2006

Mista Nishono Part III

Posted by

ジェフリー

at

11:35 AM

1 comments

![]()

Wednesday, February 22, 2006

Humbled and Hobbled

…continued from last post.

“Daijoubu desuka?” an opponent asked from above.

No, I wasn’t. I was on the floor, where – adding insult to injury – I had watched the ball roll off the rim. I don’t remember if someone tipped it in. The game was over, and I was finished – for a few weeks. Not wanting to draw attention, I quickly dragged myself to the sidelines to change clothes.  The pain was so fresh that I could walk through it before the nerves came to their senses. I unlaced my And1 basketball high tops, and peeled off sweaty socks. A fleshy bulb had replaced my left ankle. It looked like elephantiasis. A recent visit to the world’s only parasite museum (left) was still on my mind.

The pain was so fresh that I could walk through it before the nerves came to their senses. I unlaced my And1 basketball high tops, and peeled off sweaty socks. A fleshy bulb had replaced my left ankle. It looked like elephantiasis. A recent visit to the world’s only parasite museum (left) was still on my mind.

“See you next week!” Takahiro, 23, called on his way out. Yeah, right.

Everyone was heading home. I panicked. What about me? Cabs aren’t an option if unable to articulate a route (addresses alone are useless in Japan). How to obtain food if unable to walk? I can’t point at a Domino’s picture menu from over the phone. Who could help? Certainly not a doctor. I don’t have insurance here.

Biting my scarf, I faked a thumbs up to the junior high crowd murmuring in the corner about the walking wounded. Downstairs (god bless elevators), the sports center receptionist rose halfway out of her chair.

She knows it’s Friday night whenever I walk in to buy a ticket. We always exchange evening pleasantries. Her mouth parted for the usual thank you-good night, but then her eyes bulged. Lips painted red searched for words. She inhaled through her teeth. I lied again with my hands. Such a pretty face. I’ll miss seeing it for a while.

I scratched together an idea for a home remedy: tape two Coolish ice cream bags around my ankle and pray. I mean, just where was I going to get ice? Sapporo? (Look at who came in fifth!).

Forget Sapporo, even the supermarket was too far away. Instead, I shuffled into 7-11, and hobbled over to the cooler. No Coolish, but there on the bottom shelf were bags of “rock-ice for people who know the difference.” I knew. The difference was having an ice pack instead of ice cream bags to reduce swelling. Oh, thank heaven.

Forget Sapporo, even the supermarket was too far away. Instead, I shuffled into 7-11, and hobbled over to the cooler. No Coolish, but there on the bottom shelf were bags of “rock-ice for people who know the difference.” I knew. The difference was having an ice pack instead of ice cream bags to reduce swelling. Oh, thank heaven.

With morning came judgment day. The bulb had shrunk. No sign of bruising either (that wasn’t till the third day). Yet, on my way to tutor elementary school girls, a 15-minute stroll to the station became a 30-minute physical challenge.

In a perverse way, I enjoyed the humbling sensation of not taking walking for granted. Overnight I had aged 50 years. I had the gait of the local hunchbacks pushing carts of groceries whom I ordinarily zoom by when dashing to the station. Not being able to walk puts the rest of your problems in perspective.

However, I also felt like even more of an outcast. I get enough unwanted looks on the street on normal days. Now I kept a lowered head to avoid eye contact altogether. A mix of pity, curiosity and fear stared back when I looked up at intersections.

I’m not used to slowing down for the flashing green man when about to cross. I navigated the elevated walkway over the highway with right hand on the railing and left foot in the air, hopping stairs with my right foot like a Double Dare physical challenge (minus the super sloppy slime).

So young, but so crippled must have been running through the minds of passersby. Mothers steered children away from my path as I teetered along the edge of the sidewalk like a wounded animal on its last legs, clutching walls, poles and railings for support.

As usual, weekend plans included only a date with the washing machine. The ice pack accompanied me throughout the evening. I tucked myself into bed, and it into the freezer. Thank you, rock-ice. You’ll always be on hand when my foot needs you, which hopefully is never again.

Posted by

ジェフリー

at

10:00 AM

0

comments

![]()

Tuesday, February 21, 2006

The Hoop and the Harm

From playing basketball with handicapped kids to becoming one myself, my ankle took an unfortunate twist last Friday. All week I look forward to shooting hoops with locals ages 13 and up.

The Japanese are sharp shooters, but lousy defenders. When scrimmaging they seek to shoot as much as possible from as far away as possible. Yamazaki, 21, has a 3-point shot matched in meanness only by his skin disease. His preferred firing range is from between the 3-point line and half court. Swish.

The only times I touch the ball on offense are by accident or offensive rebound. I quickly pass for fear of blowing another lay up. Like the rest of Japan, rims at the ward sports center take exception to foreigners. As the lone alien on the court, I’m easy to spot.

I contribute solely on the defensive end. I patrol the oversized international key while four teammates wait to fast break back down court. There’s no set offense – just fast breaking and 3-pointer launching. Sometimes they just stay on offense. Taking cigarette breaks in between games hasn’t increased their stamina to hustle back on defense.

By 8:30 p.m. I’m ready for a break, too. I sub out 15 minutes early to take advantage of nebiki, discount food shopping, at Chiyoda Sushi. Prices are slashed up to 50% to clear the day’s inventory.

Besides, you know what they say about taking that one last run on the ski slopes. I don’t want to tempt fate in that final game for fear of injuring, well, someone else. I’m known to foul hard, going for ball or head – whichever is closer – in hopes of recording a thunderous block. Swatting the ball out of bounds with authority has caused badminton players on the opposite side of the gym to take notice.

Last Friday, however, I skipped nebiki. Goseki, 21, and always sporting New Jersey Nets gear, was telling me about his upcoming trip to NY with Yamazaki to see the Nets face the Knicks at Madison Square Garden. I frowned. He smiled and said, “Do you feel homesick?”

With about one minute left, somehow I got the ball on the perimeter. Feeling frisky, I surprised everyone by hoisting a shot. My outside touch has improved, but this attempt smacked the side of the rim with a thud. Frustration mounted at not adding to 4 points the whole night (on six shots).

Similar to Japanese shops, “closing time” music filled the gym. Fourteen all. Last play. Offense. Goseki missed a 3. I rebounded. I was too far under the basket to put it back up. I didn’t pass. Not this time. I dribbled outside, then back into the key. Three defenders converged. Pivot, fake, spin. I saw an opening, and sliced between two defenders. Jump! Airborne, I flicked the ball. Light touch. Looks good! Bouncing around on the rim. Front. Back. Bouncing…oooww –

Pain shot through my leg. I’m down. And couldn’t get up.

Did the shot fall like the shooter? Find out tomorrow.

Posted by

ジェフリー

at

10:47 AM

3

comments

![]()

Sunday, February 19, 2006

Trouble Kids

Every week at Omiyada, I am invited to spend a period with “trouble kids.” At first I hesitated. I get enough trouble at Kanokita. But when told that the “handicapped class” was looking forward to my visit, I put two and two together and quickly accepted.

Having the sole classroom on the ground floor, the boys inside inhabit a world separate from those upstairs. For one thing, it’s better furnished than my apartment: 3 laptops, 2 PCs, 2 printers, xerox machine, TV, stereo, grand piano, keyboard with mic, potted plants, humidifier, hot water machine and fridge. Not bad for a public school.

The student to teacher ratio is 1:1 – there are two of each. Omiyada offers an enriching program that dotes upon each individual. Sign me up. By contrast, about 15 special ed. students at Nubata School feel even more special by dressing not in the standard navy uniform, but in a red sweat suit to flag their status. The official reason, I’m told, is that red is easier to spot in case one goes missing. Right.

The first lesson at Omiyada was self-introduction. One boy followed up with more thoughtful questions about the U.S. and Katrina than the “normal” students upstairs.

A teacher of traditional performing arts joined our second class. The taiko master led a jam session on a drum that required two people to move while the boys banged away on two smaller ones. They sounded just as good as the performers at festivals, but here I got a private show. I resisted taking a hit. Haven’t students laughed at me enough? But drumsticks were deposited into my hands anyway. Spreading legs in the “orthodox” taiko pose, I channeled frustrations into hammering the “lady cow skin” covering the drums.

I resisted taking a hit. Haven’t students laughed at me enough? But drumsticks were deposited into my hands anyway. Spreading legs in the “orthodox” taiko pose, I channeled frustrations into hammering the “lady cow skin” covering the drums.

“Soré!” I screamed, raising my arms and then crashing them down with all my might. I aimed to pierce the drum. Hitting something this hard felt good. In what could be a first step toward group therapy, I answered a classified “calling all taiko drummers.”  Fun and games continued the third week with shogi, Japanese chess. I learned the rules while suffering a defeat at the hands of the more mentally disabled of the two boys. I avenged the loss with a narrow victory over his classmate before both teachers trounced me.

Fun and games continued the third week with shogi, Japanese chess. I learned the rules while suffering a defeat at the hands of the more mentally disabled of the two boys. I avenged the loss with a narrow victory over his classmate before both teachers trounced me.

Luckily, I had prior experience with the fourth lesson. The assignment was to create machajawan (tea bowls) to eventually have a tea ceremony. Clay caked under my fingernails and hardened on my palms, sucking moisture out of my cracking hands. I flashed back to a high school ceramics independent study. I may have lost in shogi, but my bowl was unbeatable.  It had been fired in time for the fifth lesson, devoted to sandpapering. Sanding helps smooth imperfections hardened in the firing process; however, unless you’re keen for silicosis, two years as an asbestos paralegal taught me not to grind brake pads, cut pipe covering or sand fired clay. But then again, in Japan asbestos was banned only recently. I dunked my bowl into a tub of black glaze that stained my fingertips.

It had been fired in time for the fifth lesson, devoted to sandpapering. Sanding helps smooth imperfections hardened in the firing process; however, unless you’re keen for silicosis, two years as an asbestos paralegal taught me not to grind brake pads, cut pipe covering or sand fired clay. But then again, in Japan asbestos was banned only recently. I dunked my bowl into a tub of black glaze that stained my fingertips.

Drinking from the fruits of our labor, I enjoyed piping hot green tea with sweets at a Japanese tea ceremony during our sixth class. Cheers to respiratory illness and lead poisoning.

Cultural pleasantries dissipated and competition resurfaced during our final meeting. It’s been a while since I’ve run laps in a gymnasium, but I welcomed any movement inside the unheated gym. After some interesting stretches, including one that mimicked fish out of water, we took the court for basketball shooting drills. Despite the ice-cold touch (my fingernails were purple), I swished a few.

With 10 minutes left in the period, a teacher suggested that we five play a match. Expecting 3-on-2, I was stunned to be singled out for 1-on-4: America vs. Japan. Unlike Kobe Bryant, I’m not used to being quadruple-teamed and not passing to anyone, yet also having everyone to defend.

This time, coach, there was an “I” in team. I jumped out to a 2-0 lead. I didn’t bother playing defense except to collect rebounds, whereupon I sprinted down court. Japan huffed to keep pace. “Hands up!” a teacher cried as Japan swarmed to form a wall of arms jumping for the sky. The humor proved distracting.

Tied at 4 with the bell about to ring, national honor was on the line. I sensed it. The teachers sensed it. The kids might have sensed it, but were just getting in the way and missing shots. A driving lay up at the buzzer put Team America on top for good.

Victory was short-lived. Gym was over. Trouble was about to begin. It was time for class with Mr. Nishono.

Posted by

ジェフリー

at

2:15 AM

1 comments

![]()

Labels: Omiyada

Tuesday, February 14, 2006

Red Day

“Jefu, stop!” commanded an 8th grade girl. I obeyed out of surprise. I had exactly 35 seconds to get to my seat in the teacher’s room before the bell sounded the morning meeting. She took precious moments to dig out a small bag of sweets from a shopping bag.

“Jefu, stop!” commanded an 8th grade girl. I obeyed out of surprise. I had exactly 35 seconds to get to my seat in the teacher’s room before the bell sounded the morning meeting. She took precious moments to dig out a small bag of sweets from a shopping bag.

How could I forget? It was Valentine’s Day. Another girl scouting out boys from the stairwell presented me with a bag of mini-brownie squares. This being Japan, the packages were sized proportionately—three bite-sized sweets in each. 12 seconds. I could have amassed a month’s worth of dessert samples had I hung around for their friends to also open their hearts to sensei.

Valentine’s Day in Japan is a spin-off of the Western tradition. Cards aren’t exchanged, but it’s almost obligatory for schoolgirls and OLs (office ladies) to dispense sweets to their male counterparts, regardless of affection. That’s how I scored premium Kobe truffles from a math teacher, and a box of six chocolates from a private student.

Men sit back and let the loot roll in. Until March 14, that is. In a savvy ploy by confectioners (think of the Simpson’s episode where Hallmark devised a new summer card-giving holiday), on White Day men must return the flavor with white chocolates symbolizing pure feelings (or so I read in a book). A month is plenty of lead time to make good on IOUs. Luckily I’m not working then, so for me the flow is one-way. Delicious.

Or disgusting. That’s how one girl introduced her offering in bag festooned with four leaf clovers. Only in Japan…or Ireland.

In another moment of puppy dog love, on Friday I received two love letters. It was my last day at Omiyada School, which proved too much for two 8th grade girls to bear. To be sure, I think they were just appreciative to have received pink New York pencils during an overstock fire sale their final class. Shortly before I walked off school grounds forever, they tracked me down and, giggling, handed me slips of paper folded with origami precision. They even attempted to emote in English. I made sense of the Japanese by slowly sounding out the hiragana, which drew curious (jealous?) stares from semi-retired salarymen on the 15:06 train home.

Shortly before I walked off school grounds forever, they tracked me down and, giggling, handed me slips of paper folded with origami precision. They even attempted to emote in English. I made sense of the Japanese by slowly sounding out the hiragana, which drew curious (jealous?) stares from semi-retired salarymen on the 15:06 train home.

Here’s a rough translation:

Dear Mr. Jeff, First letter. Hell. Mr. Jeff's class is enjoyed. Thank you very much for the pen. I had fun. From now, thank you very much. Please don’t forget me.

Hello. My name is Shiori. From today, I enjoyed talking with you a lot. Thank you very much. I will never forget you. Thanks for the pencil. I love you.

If you're reading, girls: kochira koso. Same to you.

Posted by

ジェフリー

at

9:45 AM

2

comments

![]()

Thursday, February 09, 2006

A Case of Pen English

A pen or pencil case is a Japanese student’s best friend (after a cell phone, of course). All have one as if it’s some kind of decree from the board of education. I even used it as a word in hangman (click on photo). Puma and Mizuho corner a quarter of the market. Many bags are adorned with dangling trinkets or charms, which are often Disney or Japanese anime.

A pen or pencil case is a Japanese student’s best friend (after a cell phone, of course). All have one as if it’s some kind of decree from the board of education. I even used it as a word in hangman (click on photo). Puma and Mizuho corner a quarter of the market. Many bags are adorned with dangling trinkets or charms, which are often Disney or Japanese anime.

After investigating the desktops of nearly 1,000 students, below are the top 15 incongruous English phrases printed on students’ pen cases:

15. Sweet Cool Apple Jam

14. Baby Young Deer Bean Bags

13. I Love My Life

12. Supper Happy Girl

11. Happy Love Boy

10. Lovers Girl

9. Happy Memorial Sky

8. Dangerous Zone

7. My Enthusiastic Heart Feeling Season

6. A Good Day Is Expected to Begin! A Wonderful Presentiment

5. How About Exploring Some Unknown Spots Or Passing Through Tempting Byways

4. Milky Star

3. Milky Berry – They Hear Only Pleasant Sounds

2. One Day They Attacked, Many Bees. Romp Fighted Bravely Against Bees.

1. Please Eat Me

Posted by

ジェフリー

at

6:00 AM

3

comments

![]()

Labels: teaching (general)

Monday, February 06, 2006

Lucky Charms

A late model BMW 330 series honked at me. My ride was on time. “Where we goin’?” Hiro rolled down the window and shouted at me outside of the Nakagawa sports center where we had met one Friday night playing hoops.

A late model BMW 330 series honked at me. My ride was on time. “Where we goin’?” Hiro rolled down the window and shouted at me outside of the Nakagawa sports center where we had met one Friday night playing hoops.

I welcomed the change of plans after Mike from Flamingo agency called to say that I hadn’t passed photo selection for the soccer movie. I brushed off my bruised ego, and instead pretended to look forward to spending Saturday at the radish festival in Asakusa. Thankfully that wouldn’t be necessary.

“Takasu-Takasa-Takasomething,” I said fumbling for my guidebook. “Takasaki!”

“Where the hell is that?”

“Gunma prefecture.” (Think New York’s Dutchess County.)

“Gunma!” Hiro boomed, as if I had suggested driving to Hokkaido, Japan’s northern island.

If we left now, I explained that we’d arrive just in time for the end of a festival. The poor timing or 115 km (70 miles) trip weren’t problems. Hiro was up for driving anywhere. But if we were gonna go to Gunma, he needed maps. “This is my daddy’s car. He doesn’t know how to use GPS so there isn’t one here,” Hiro said. I smiled every time the 29-year-old referred to his “daddy.” Educated in Colorado, Hiro quit his import-export auto parts job the day before, and was now helping out at his daddy’s ramen shop two stations away from me. Sitting comfortably in the BMW’s leather interior, I assumed business was boiling over.

“This is my daddy’s car. He doesn’t know how to use GPS so there isn’t one here,” Hiro said. I smiled every time the 29-year-old referred to his “daddy.” Educated in Colorado, Hiro quit his import-export auto parts job the day before, and was now helping out at his daddy’s ramen shop two stations away from me. Sitting comfortably in the BMW’s leather interior, I assumed business was boiling over.

Highway tolls (emphasis on high) made the trip about as expensive as a slow train, but German automotive engineering beats the wheels off Japan Rail. The air was crisp; we were in the countryside. An elementary school cashed in by transforming its dirt playground into a parking lot where streams of festival-goers were returning to their cars laden with armfuls of daruma dolls. Takasaki is the birthplace of these good luck charms that represent a famous Zen monk. Legend has it that after meditating in a cave for nine years, he lost use of all limbs. This city of 240,000 manufactures 80% of Japan’s limbless, mustached dolls with vacant white eyes. They are purchased in the beginning of the year, and one pupil is painted when a wish is made. The other is added when the wish comes true. At the end of the year, the doll is returned to its shrine of origin and ceremonially burned.

Takasaki is the birthplace of these good luck charms that represent a famous Zen monk. Legend has it that after meditating in a cave for nine years, he lost use of all limbs. This city of 240,000 manufactures 80% of Japan’s limbless, mustached dolls with vacant white eyes. They are purchased in the beginning of the year, and one pupil is painted when a wish is made. The other is added when the wish comes true. At the end of the year, the doll is returned to its shrine of origin and ceremonially burned.

Hiro was huffing at the top of the 100 stairs leading to Shorinzan Temple. The daruma doll festival had lasted all night.  We arrived as vendors were packing up, but just in time to snatch up bargains on merchandise and the last batch of tako yaki dripping in barbecue sauce. There’s nothing like fried batter balls of octopus bits to send my stomach into gastronomic bliss.

We arrived as vendors were packing up, but just in time to snatch up bargains on merchandise and the last batch of tako yaki dripping in barbecue sauce. There’s nothing like fried batter balls of octopus bits to send my stomach into gastronomic bliss.

The round dolls piled on top of one another reminded me of pumpkins at the country market. Like pumpkins, daruma came in assorted sizes. And when in Takasaki…well, I wanted the biggest one my thin wallet could support.  Hiro helped negotiate, and I walked away holding one with both hands. I named it Takaruma, and bought him some smaller friends.

Hiro helped negotiate, and I walked away holding one with both hands. I named it Takaruma, and bought him some smaller friends.

“The girls in the countryside have better fashion than girls in Tokyo,” Hiro said as we walked down the mountain and passed two sets of short skirts and long legs shivering in the dead of winter. “But country girls can be shy.” Although married, he sometimes calls after the uniformed high school girls.

We decided to explore downtown. Leaving Starbucks, a rainbow-colored sign in English caught my attention. “We Go used clothing 7F.” I was feeling lucky already having purchased charms in bulk. “Can we go?” I asked, persuading Hiro to scale seven flights of escalators to take a closer look.

I was in luck. The store was having its January 50% off sale. Worker jackets stitched with random nametags hung on a rack outside the entrance. Parting the hangers, I saw myself. “Hey Jeff, can you fix my flat?” Hiro joked. I shared first names with an employee of Sterling trucks (or plumbing). It fit well, and my green tea frappuccino cost nearly as much. The sales clerks’ eyes widened at the novelty of the match.

The music inside was thumping, and I could tell that Hiro wanted to get out of Gunma and back to the city. I re-racked a burgundy velvet blazer, and after a fruitless detour to HMV in the basement, we bid Gunma goodbye. Takasaki’s lights twinkled in the sunset.

View the Daruma slideshow here.

* * *

The only flaw with the jacket was its wrinkled fabric. Hiro suggested pressing it at the cleaners. The label confirmed that dry cleaning was an option.

But after wishing me a happy New Year, the fatherly owner of Fashion Cleaners said he couldn’t help me. So, I walked down the block for a second opinion. A voice welcomed me from the depths of racks of clothing wrapped in plastic, but trailed off upon seeing a foreigner.

I apologized in Japanese for not speaking Japanese, and used gestures to indicate I wanted the wrinkles removed. This prompted the woman to talk up a storm. I deduced that she couldn’t help me either, and that it had to do with the polyester and cotton shell.

I humbly admitted I didn’t understand one word of what felt like a three-minute explanation. She asked me where I was from and why didn’t I understand Japanese (this I did understand). “It’s hard,” I conceded, continuing to stretch out the fabric to make the creases disappear. I wanted them out. This sparked more babbling. It must be the ESL teacher in me, but when I know that a listener doesn’t understand much English, I talk as slowly and simply as possible.

“It’s hard,” I conceded, continuing to stretch out the fabric to make the creases disappear. I wanted them out. This sparked more babbling. It must be the ESL teacher in me, but when I know that a listener doesn’t understand much English, I talk as slowly and simply as possible.

This woman had no such sympathy. I watched her mouth like a spinning slot machine, waiting to match up three recognizable words in a row and cash out. The best I could determine was that the material couldn’t be ironed, and that the jacket looked cool the way it was.

Wrinkled or not, this ¥750 ($6.50) jacket is actually warmer than the spring shell I’ve been skating by on to shield against winter. After I make a few house calls around the neighborhood, I’ll earn enough to upgrade to proper gear. Now if you’ll excuse me, I think I hear the muffler or toilet tank running.

Posted by

ジェフリー

at

1:45 AM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: domestic travel, festivals

Thursday, February 02, 2006

The Elective Class

Only one period stood between a typical weekend of doing nothing and the end of teaching at Omiyada for the week. It was an elective class with 9th graders who had signed up to improve their English, at least in theory. I had taught them once before, but couldn’t remember. Thus, Mr. Nishono forewarned me of their low ability, but added that they didn’t “misbehave as badly” as other classes. He was right about their language skills.

I chuckled at “seX’mas,” a now unseasonable joke still on the board. The classroom was seldom used. As a result, I broke out in goosebumps. A space heater in the front of the room offered little relief. A boy with a shaved head shaped like a phallus (no, really), picked up chalk and drew a naked woman spread eagle with hardened nipples. Yes, it was that cold. The picture was manga (comic book) quality, but I censored it before Mr. Nishono got around to focusing his glasses on something other than the floor.

While the fifteen students may have elected to take an extra class of English, they clearly had other plans for the period. Mr. Nishono labored to pass out a sheet of irregular verbs to be conjugated in the past tense. It was a hopeless challenge. Monkey Boy and a friend with the intelligence of a banana peel sat in the back, shredding the handout with a pizza slicer-like like tool I recognized from the ceramics studio.

I encouraged students to trade their frivolous pursuits for verb conjugations. I looked to Mr. Nishono for support, but discovered that he was no longer with us. I asked phallus-head boy if he knew of his whereabouts. “Masturbation,” he said calmly without looking up from sketching, fittingly enough, various sized phalluses (yes, really). Doubtful, I thought, unless he stocks Viagra in chalk case.

“Do you eat girl? Do you like sex?” phallus-head then chirped with a mischievous grin. Before turning my back, I slipped him a piece of chalk as creative license to amuse me on a larger canvas.

Mr. Nishono returned 10 minutes later. He sat down to chat with two girls in the back. He soon closed his eyes and stopped moving. If he wasn’t going to take class seriously, then neither was I.

So, if you can’t teach ’em, join ’em. After writing “1. bought 2. visited 3. carried…” on the board, I joined two boys huddled by the heater and checked on their drawings. One drew two circles. “Meatballs,” I said. He then sketched a “sausage” in between them. To finish off the meal, he added curly wisps, and pronounced, “spaghetti.” We both laughed hard. Thankfully, this was after lunch, the special having been – you guessed it – with meat sauce, cucumber, egg and spinach toppings.

Posted by

ジェフリー

at

10:55 AM

0

comments

![]()