Kanokita School is laid out in a horseshoe. Characterless five-story buildings surround a central courtyard with a gated entrance. Every morning, teachers, PTA members, and the principle greet students at the gate as per Japanese custom. They also serve as a checkpoint to inspect hair length, uniform collars and buttons, and to deaccessorize jewelry. Makeup is also forbidden.

Bowing on the run, I utter a hurried “ohayo gozaimasu” to the greeters two minutes before the bell chimes. The courtyard leads to the main building where faces suddenly appear in half-open windows. Hands poke out like little prisoners in the county jail. “Ooh Jeffurey!” they crow while waving to me and smirking to their friends – probably about my commuter tennis shoes or funky tie. This ritual occurred each morning on the way in and afternoon on the way out.

Walking out on my last day surely would be memorable. A scream rang out from the fourth floor window. I recognized a boy with no English skills hanging his mini-mohawk outside.

“Fuck you!” he shouted.

His words rained down on me like bricks. My heart pounded. Pride bubbled inside. What excellent intonation and diction! His English had definitely improved. I congratulated him with a salute of the middle finger, and laughed all the way to the bus stop shedding a tear of joy.

Well, at least that’s how I envisioned my grand exit from one of Tokyo’s most dysfunctional public schools. At Kanokita, however, such insolence only qualified for a regular day. This one was a Wednesday in September.

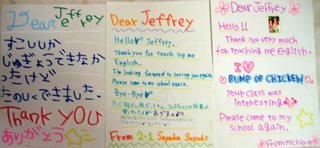

In reality, while counting down the final hours, Ms. Hattori dropped a stack of papers on my desk. I gave her the look. I didn’t do grades, and it was a little late for lesson planning. I looked down again. Suspicion melted into surprise.  This was the lesson plan! Students had spent a period decorating goodbye letters in rainbow ink. My heart tingled like when someone unexpectedly remembers your birthday. The stack was too thick to review on the spot, so I peeked at a few and savored the rest on the commute home.

This was the lesson plan! Students had spent a period decorating goodbye letters in rainbow ink. My heart tingled like when someone unexpectedly remembers your birthday. The stack was too thick to review on the spot, so I peeked at a few and savored the rest on the commute home.

I hunted down several students to pass out the remaining pictures I had snapped of them over the course of the year (as a cover for my ulterior motive of posting them online). I couldn’t recognize some because heads sprouting bushy hair in the photo stood before me cleanly shaven and vice versa.  It was now after 5:00. I had never stayed at school this late. A lone flute trilled somewhere down the hall. Dribbling echoed in the gym. The tranquility of after school clubs reigned in the absence of daytime mischief-makers. I joined the basketball team for a few lay-ups and blocked shots. Students gathered to give me a last round of high-fives.

It was now after 5:00. I had never stayed at school this late. A lone flute trilled somewhere down the hall. Dribbling echoed in the gym. The tranquility of after school clubs reigned in the absence of daytime mischief-makers. I joined the basketball team for a few lay-ups and blocked shots. Students gathered to give me a last round of high-fives.

“What’s my name? What’s my name?” a boy in a black Nike t-shirt asked with Destiny’s Child-like insistence. I could only pat him on the head. Kohei was quick to remind me.

“Good luck, Kohei,” I said as our brown eyes connected. “And practice your English, okay, buddy?” Our palms smacked together one last time.

Pushing through the creaking metal gate, I walked out of the courtyard and toward the bus. I reached into my bag for headphones. Just as I was about to juice up my iPod, I thought I heard the wind whisper my name. I turned around. It was Kohei.

“Jeff-uh-ree, Jeff-uh-ree byee-bye!”

The final farewell. For the third time. It was just like the ending of a romantic movie – except that we weren’t in love. We were partners. Partners in a cross-cultural exchange whereby they heard a native English accent without a CD player, and I vicariously experienced Japanese adolescence (going through puberty once firsthand was more than enough).

Kohei, shivering in basketball shorts under darkening March clouds, suddenly represented the hundreds of students I had stood before with an open textbook. The dozens who made me laugh with their “Japanglish” or universal acts and words of immaturity. And the handful who touched my heart with their gentle personalities and genuine interest in English or America.

Beyond textbook scripts and the supervision of other teachers, exchanging a spontaneous sentence or two with these special youngsters made the day’s commute worthwhile. It made the move to Japan worth the effort. Kohei was the last one of them that I’d ever see, ever interact with. He stood there smiling and waving like a happy dog.

I waved back and walked backwards. I couldn’t see the Swoosh on his shirt anymore. My eyes were misty. The setting sun and approaching cold front cast an eerie orange glow. Heaven’s tears showered the bus just as I boarded.

Thursday, June 29, 2006

Last Day

Posted by

ジェフリー

at

4:45 AM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: Kanokita

Friday, June 23, 2006

Nuts for Nuts

“Hello, how are you?” plays like a broken record from my lips during school hours. The next most uttered phrase is “Don’t touch me!” Unfortunately, it’s yielding diminishing returns.

Students now mimic me as they swarm in to cop a feel. What would be viewed as perverted or queer in America seems perfectly playful among touchy-feely Japanese school boys. The progression of the school year has only fueled their aggression for my receiving unwanted attention.

The final days of my tenure as a public school assistant language teacher bore an unprecedented number of bold attacks on private parts in public places. After lunch with one of my favorite classes, the boys were feeling frisky. There had been grabbing before, but not like this. Had there been something extra saucy in the fish cake lunch?

I enjoy mingling with students in the unstructured 20 minutes that follow lunch, but as a spectator manage to stay above the fray of pile-ons, insect-catching and games of onigokko (cops & robbers). Not today.

Larger classmates were preying upon “little angel” (my nickname), the smallest and most adorable boy of the class. He was in the fetal position on the floor protecting his vital organs and sacrificing his shoes in the process. I stepped in to repossess his footwear, but was suddenly swept up in what could only be described as a round robin kancho free-for-all.

“Clitoris!” the naughtiest of the mob shouted, catching me off-guard and scoring a direct hit (grab) on my crotch. I cursed him off in English, and side-stepped a second strike. The halls echoed with the frenzy of high-pitched screams and squeaking sneakers as the boys turned on one another.

“This is new sport,” one boy said rushing by with an outstretched hand in pursuit of his friend. I cautiously slid to the nearest stairwell. If kancho were an Olympic sport, I’d award Japan the gold.

* * *

English words were the last thing the boys in the back were penciling into their notebooks. One sketched a picture of a boxer with oversized gloves and long, wavy hair. When I walked over, he labeled it Jeff. He then asked for vital stats to accompany the diagram.

“I’m 185.3 cm. Taiju is 70 kg...what did you say? You little pervert!” I slapped him on the head. Here we go again, I thought, but this time was different. His friends coordinated a two-prong attack. One lunged for the front while the artist reached for the rear.

They took stabs at the American flag erasers I was holding. One snatched it out of my hand and wouldn’t return it, only offering to arm wrestle for it. Intimidated by his spiky hair and shaved eyebrows, I let him keep it.

I looked up to the front of the room to call for backup, only to find that the Japanese English teacher had already left. I looked back down. The artist pulled out a ruler, pressed it against my upper thigh and scribbled a measurement in his notebook.

* * *

I always walk around on high alert when in the presence of Kanokita 7th graders. Although the nickname applies to many, one kid tries so frequently that I’ve dubbed him “The Crotch-Grabber.” This picture caught him in the act. (The green and white sleeve is outstretched to ward off the attack). Today’s class was handing back midterms full of red ink. The student who scored a 96 was sculpting dried flakes of white out into lines on his desk. Kenta scored a 4. He already drew my sympathy as the class shrimp, always looking lost behind long hair that curled on his neck like the crustacean’s tail.

Today’s class was handing back midterms full of red ink. The student who scored a 96 was sculpting dried flakes of white out into lines on his desk. Kenta scored a 4. He already drew my sympathy as the class shrimp, always looking lost behind long hair that curled on his neck like the crustacean’s tail.

“Thirty-five?” Crotch-Grabber whined as he crumpled the paper. Devoting more attention to vocab lists instead of my groin would surely increase his rank.

After class, Crotch-Grabber found me in the hall. One wrist was bandaged, which I thought would slow him down. It only increased his ingenuity. He faked his hand down and pinched my nipple. I yelled. The crafty kid offered me a high-five apology, but instead gave me a low grab.

A passing teacher laughed it off as cute, but I didn’t think it was so funny. I wrapped my hands around his neck and pushed him into a corner. Then the tables turned. It happened fast. His friend swooped in for a hit, allowing Crotch-Grabber to break free and renew the assault. I blocked, but our arms tangled. My ankle turned. I didn’t know how to tell him it was still in bad shape after a basketball injury a few weeks before.

To take the pressure off, I leaned on my other ankle, but balance befell me and I took Crotch-Grabber down with me.

“It hurts!” he yelped in Japanese while clutching his bandaged arm that I had just landed on. Nervous and apologetic, I put my hand on his shoulder. Grinning, he slugged his free fist into my crotch.

Posted by

ジェフリー

at

10:30 AM

0

comments

![]()

Tuesday, June 06, 2006

Editing History

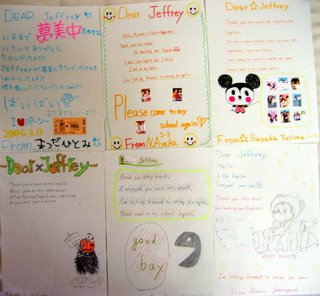

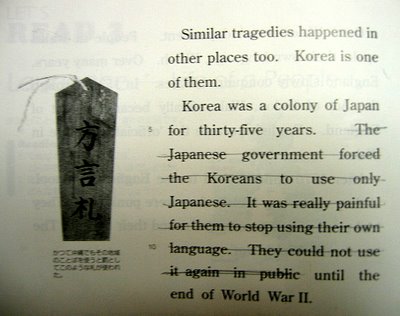

Aside from Prime Minister Koizumi’s yearly pilgrimage to Yasukuni Shrine, there's nothing that embitters Japan’s neighbors more than its Ministry of Education’s approval of textbooks. Every few years when an update is due, a renewed uproar ensues accusing Japan of whitewashing its role in history. Last year was one of those years.

Although I teach in public schools, I’m not proficient in Japanese, and never thought I’d witness the controversy first-hand. That is, until I was modeling dialogue for a lesson about “Language – Life of a People.” It was the last lesson in the 9th grade English textbook, and discussed how after 1870 the Welsh were forced to use English in school, and were punished if they didn’t. The next example hit closer to home by bringing up Japan’s restricting the use of Korean during its occupation of the peninsula. The teacher stopped me in mid sentence. Was I speaking English wrong? It turned out that the government-approved textbook (used in all of Tokyo’s public English classrooms) had been gussied up (I mean, updated) just after publication. I was reading from the old version. Contrast it with new one below:

The teacher stopped me in mid sentence. Was I speaking English wrong? It turned out that the government-approved textbook (used in all of Tokyo’s public English classrooms) had been gussied up (I mean, updated) just after publication. I was reading from the old version. Contrast it with new one below:

“…Korea was a colony of Japan for thirty-five years. Korean school children had to learn Japanese as the ‘national language.’ Later, Korean language classes become optional. It was really painful for them. This system lasted until the end of World War II.”

You be the judge.

Posted by

ジェフリー

at

11:40 AM

1 comments

![]()

Labels: teaching (general)

Friday, June 02, 2006

Money Hungry

“Money and Card” was the title of the final lesson with Mr. Mochizuki. Preparation was simple: wow the kids with faces of dead presidents on American currency. I brought a dollar’s worth of new pennies to Japan to inspire interest in American culture, and as backup should pencil prizes become exhausted.

The first student to guess the value of the coin I held up received a cash prize. Like ravens, shiny coins distracted 7th graders. I wasn’t so generous with the bills. I weighted down $1, $5, color $10, and $20 notes on the front desk with piles of pennies, and called up rows of students for a viewing. Their eyes turned green, and begging began.

Upon realizing that I was lax about their taking centy souvenirs, they got greedy. They clamored for something I walk away from when dropped. There were a lot of outstretched palms to grease. One kid reacted after smelling a fistful of change. Yup, smells like America all right. Japanese currency is somehow odorless.

I brandished a credit card to regain the educational focus of the lesson. This only stirred the pot. Visa is not everywhere you want to be in this cash-based society, and I transformed from assistant teacher to Daddy Warbucks. The bell rang before I could count my change, but by then it was too late. About 25% of the kids made off with 75% of the coins.

I stuffed the bills, card, and a few remaining dimes into pockets while shaking off demands for more. I continued to laugh until they started poking in places I didn’t wanted to be touched. One pilfered the bag of coins from my rear pocket. I beat him on the head with the textbook until I got a refund.

I consolidated valuables into the front pocket and made for the door. Three kids blocked my path. I sliced through them, but two more held the door shut. I needed backup, preferably an armored car, but even the bumbling Mr. Mochizuki would do. He had already left, and I had to fend off the mob alone.

Driven by hormones and greed, they groped and grabbed – my pockets, buttocks, anything they could get their dirty little fingers into. Outnumbered and outmaneuvered, my bum ankle only hampered my agility.

They were swarming now. Desperation swelled in my gut. I went into survival mode, and backed into a corner. One tried to sneak behind me, so I used my hips to check him into a metal cabinet. He yelped, holding his hand in pain. Others reached in for the “arm”ed robbery.

I knocked two boys out of the way, and broke for the back door again. The kids exited from the front, and confronted me in the hallway. Once there they suddenly became like fish out of water. Although their momentum died, it wouldn’t be the last time they tried to make off with my jewels.

Stay tuned for “Nuts for Nuts”….

Posted by

ジェフリー

at

7:00 AM

0

comments

![]()