Not one to turn down a party invitation, I met Yuji at the Roppongi station turnstiles. This area of town pulsates at night under neon signs advertising sweaty bars and decadent companion clubs. A haunt of tourists, expats, military and the Japanese who wanna party with them, I avoid Roppongi’s $9 beers and cheesy music at all costs.

Not one to turn down a party invitation, I met Yuji at the Roppongi station turnstiles. This area of town pulsates at night under neon signs advertising sweaty bars and decadent companion clubs. A haunt of tourists, expats, military and the Japanese who wanna party with them, I avoid Roppongi’s $9 beers and cheesy music at all costs. Yet Yuji’s friend was DJing, and I figured it would be a good chance to hang out outside of his father’s tiny restaurant where we had met. I’m glad I made the exception. Yuji’s limited English could not prepare me for what type of party to expect. To play it safe, I wore a button down shirt stuffed into slacks. I should have remembered that Japan doesn’t have a dress code.

Yet Yuji’s friend was DJing, and I figured it would be a good chance to hang out outside of his father’s tiny restaurant where we had met. I’m glad I made the exception. Yuji’s limited English could not prepare me for what type of party to expect. To play it safe, I wore a button down shirt stuffed into slacks. I should have remembered that Japan doesn’t have a dress code.  Yuji (right) – in baggy pants, a grey hooded sweatshirt and wool cap – led me in the opposite direction from the bright lights. We made a Family Mart run to grab drinks to finish off en route. The stairwell descending into the basement bar was dizzying. Graffiti lined the walls down to the bottom where a lanky DJ (center) welcomed me like an old friend, and handed out a CD with his R&B remixes.

Yuji (right) – in baggy pants, a grey hooded sweatshirt and wool cap – led me in the opposite direction from the bright lights. We made a Family Mart run to grab drinks to finish off en route. The stairwell descending into the basement bar was dizzying. Graffiti lined the walls down to the bottom where a lanky DJ (center) welcomed me like an old friend, and handed out a CD with his R&B remixes. The bonenkai wasn’t starting for another half hour. This marvelous Japanese concept is known as “year-forgetting parties.” (This being back in December). Momo was already forgetting. He wobbled around the room in a large reindeer headgear. Yuji meanwhile posted flyers with the DJ lineup around the bar.

The bonenkai wasn’t starting for another half hour. This marvelous Japanese concept is known as “year-forgetting parties.” (This being back in December). Momo was already forgetting. He wobbled around the room in a large reindeer headgear. Yuji meanwhile posted flyers with the DJ lineup around the bar.

I was the only foreigner in attendance, which is how I like it. It feels more cultural in that lost in translation way. I get C-list celebrity attention, and don’t get annoyed with other foreigners who think they are god’s gift to Japan for being proficient in the language.

I did, however, feel conspicuously overdressed among the music video wannabes in oversized off-brand tracksuits, dangling chains and sunglasses – sometimes a sign of gang membership here. Then again, it’s hard to consider someone wearing size 28 pants as tough, especially with a Louis Vuitton wallet poking out of the back pocket. Sometimes they’d catch me staring with arced eyebrows at their outfits, but as a foreigner I can get away with it by falling outside of the Japanese social rubric. A smile and head nod turns embarrassment or confrontation into an icebreaker.

Sometimes they’d catch me staring with arced eyebrows at their outfits, but as a foreigner I can get away with it by falling outside of the Japanese social rubric. A smile and head nod turns embarrassment or confrontation into an icebreaker.

Such was the case with Kobe. I forget his real name, but he was wearing the basketball star’s jersey with matching Lakers cap and a fake gold chain that read “chain gang.” This Yokohama boy was no Bay Star. He looked the least likely of anyone in the room to play a sport or be in a gang. Yet he was eager to make my acquaintance, and summoned his friend Nao to join us. Long hair poked out of Nao’s trucker’s hat that read “No problem. I love working my butt off for no money.” His sweatshirt was two sizes too big, and he had a goofy grin like he had been sniffing too much glue. He was an older but just as immature version of my students. He even lived in the same neighborhood. Astonishingly, he too, had wandering hands. I’m beginning to think this is a latent cultural phenomenon.

Long hair poked out of Nao’s trucker’s hat that read “No problem. I love working my butt off for no money.” His sweatshirt was two sizes too big, and he had a goofy grin like he had been sniffing too much glue. He was an older but just as immature version of my students. He even lived in the same neighborhood. Astonishingly, he too, had wandering hands. I’m beginning to think this is a latent cultural phenomenon. Like most people I met that night, Nao had a curiosity for English. First about translations for private parts, and then about his hat. “Butt” was easy enough, but the expression wasn’t. What did working hard have to do with a butt? he wanted to know. Giving up in frustration, I asked to borrow the hat to wear to the next monthly teachers’ meeting.

Like most people I met that night, Nao had a curiosity for English. First about translations for private parts, and then about his hat. “Butt” was easy enough, but the expression wasn’t. What did working hard have to do with a butt? he wanted to know. Giving up in frustration, I asked to borrow the hat to wear to the next monthly teachers’ meeting.

I also had trouble translating “Shat,” the artist’s name on the flyer advertising the evening’s party. This being a country where M-Shit is a popular punk rocker (M stands for Mohawk. Shit, for talent).

Easier to explain was a baby blue Columbia varsity jacket, purchased second-hand and turning baby brown from a patchwork of stains. Kousuke was startled to learn that Columbia was a university in New York. I was startled to see it personalized with “Christie.”

Unable to translate songs titles like “Return of the Mack” and “Bug A Boo” or lyrics like “Can I have it like that?…You got it like that,” Nao suggested that we not pay bar prices and instead drink on the sidewalk outside Family Mart. While not illegal, it felt amateur…and freezing, this being winter. Back inside, Momo (right) was slumped over, naked without his headgear and neglecting the hot plate simmering with pre-cooked hot dogs on sticks for sale. More people had arrived, and Yuji facilitated introductions.

Back inside, Momo (right) was slumped over, naked without his headgear and neglecting the hot plate simmering with pre-cooked hot dogs on sticks for sale. More people had arrived, and Yuji facilitated introductions.

The underground setting bred intimacy. The vibe was friendship, not meat market, which is the selling point of foreigner hangouts in nearby Roppongi. Everyone seemed to know one another like we were in a party in a friend’s basement party.  The dance floor got crowded. Passionate DJs moved their friends with homespun music. In typical Japanese style, no one was going overboard. No bumping ‘n’ grinding, just bopping in place. Fly swatter-like arm extensions towards the DJ signaled approval. Some added their own beat with two drums on hand for audience participation.

The dance floor got crowded. Passionate DJs moved their friends with homespun music. In typical Japanese style, no one was going overboard. No bumping ‘n’ grinding, just bopping in place. Fly swatter-like arm extensions towards the DJ signaled approval. Some added their own beat with two drums on hand for audience participation.

In between DJ sets, live acts took the stage. Japanese rappers wearing puffy jackets and unbent MLB lids sang a good first number. Of course, I didn’t understand a word, but the same goes for American rappers. It was refreshing to be with an unpretentious crowd enjoying one another’s company to amid good soundtrack. No drama, just a girl in a Santa costume passing out free shots of fizzy tequila. It was also DJ’s birthday, and at the end of his set he was presented with a cake, which everyone devoured using a communal spoon.

It was refreshing to be with an unpretentious crowd enjoying one another’s company to amid good soundtrack. No drama, just a girl in a Santa costume passing out free shots of fizzy tequila. It was also DJ’s birthday, and at the end of his set he was presented with a cake, which everyone devoured using a communal spoon.

Santa and reindeer girls made a festively adorable duo, Nao was a one-man comedy show, but DJ was my favorite. He didn’t know much (any?) English, but his smile was contagious. The turntables electrified his blood. I could only feel excited watching him bounce around the DJ booth waving records in the air. He hooked me on “The Drive” by Headnodic & The Procussions and a Chemical Brothers remix of “Galvanzie.” Rock on, DJ. This being a monthly party, I’ve gone several times since December’s debut, hence pictures in different clothes. The flowers were from Maki for my birthday. Viewers will be pleased to know that I’ve since done away with the long hairdo. I don’t know what I was thinking other than that it was winter and my head was cold.

This being a monthly party, I’ve gone several times since December’s debut, hence pictures in different clothes. The flowers were from Maki for my birthday. Viewers will be pleased to know that I’ve since done away with the long hairdo. I don’t know what I was thinking other than that it was winter and my head was cold.

Thursday, July 27, 2006

Hey Mr. DJ

Posted by

ジェフリー

at

6:15 AM

1 comments

![]()

Sunday, July 23, 2006

Mandalay on My Mind

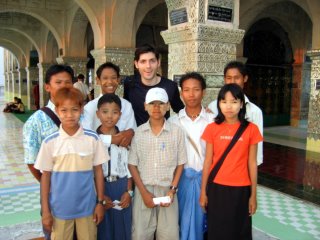

Once in Mandalay, I reunited with Erin & Miles, fellow American traveling buddies I had met in Yangon. They had taken the overnight bus, and after hearing stories of a flat tire, midnight military checkpoints, and sub-zero degree air-con, I concluded that the train was the lesser of two evils. For sunset, we headed up Mandalay Hill. During our barefoot half-an-hour climb, we encountered a group of “students” ages 13 to 18. We had heard this story before. I thought they were hustlers, but was quickly proved wrong. One boy even bought me a bracelet. Others clutched a printout with questions to ask tourists to practice their English. They seemed thrilled to talk to Americans. Not many native English speakers care to visit a military dictatorship with a history of human rights violations.

For sunset, we headed up Mandalay Hill. During our barefoot half-an-hour climb, we encountered a group of “students” ages 13 to 18. We had heard this story before. I thought they were hustlers, but was quickly proved wrong. One boy even bought me a bracelet. Others clutched a printout with questions to ask tourists to practice their English. They seemed thrilled to talk to Americans. Not many native English speakers care to visit a military dictatorship with a history of human rights violations.

These kids, however, made me glad I broke rank. A 360-degree panorama of the plains greeted us at the top. While other tourists took pictures of the sunset, we Americans gathered the children in a circle and began an impromptu lesson with their undivided attention. I introduced the concept of ‘high-five,’ which we practiced many times.

The walk down was dark. Flickering electricity teased our eyes. At the bottom of the hill we met their 22-year-old teacher. He invited us to class the next evening at a nearby monastery.

* * *

After an ambitious day visiting the ancient cities of Paleik, Inwa, and Amarapura via private taxi, we returned to Mandalay. The sun was done, but teaching duties remained.

The darkened road had no signs, but we knew we had the right place. Headlights illuminated joyous expressions of kids waiting at the monastery’s gate. Apparently, we were the only foreigners who had ever taken up the invitation. The teacher was ecstatic, too, and kept apologizing for the blackout. Although they were scheduled to have power that evening, candles had to be lit. Thirty of us gathered on the floor of a main hall with a huge Buddha statue. I had never envisioned a lesson without a board, much less lights. Suddenly the latter materialized, and Miles took over with charades. It spawned a teaching revolution.

Thirty of us gathered on the floor of a main hall with a huge Buddha statue. I had never envisioned a lesson without a board, much less lights. Suddenly the latter materialized, and Miles took over with charades. It spawned a teaching revolution.

Older students cornered me in the back with questions. When I wrote down words like “amazing,” “gorgeous,” or “guinea pig,” notebooks jostled to copy it down. I couldn’t pay Kanokita kids to do that. Those studying for less than two months had better vocabularies than second-year Japanese students. One surprised me with “nunnery.” I guess vocab lists are different in Buddhist countries (yes, Japan has Buddhists, too, but nothing like Burma).

Learning from the mistakes of the Japanese school system,  I decided to divide the group based on ability. Miles, Erin, and I each took a group. Erin took the newest learners. Miles (right) got Lai Nu, among others. I got the boy with the orange spiky hair (left) and Konnai, the one with the best yellow thanaka design on his cheeks.

I decided to divide the group based on ability. Miles, Erin, and I each took a group. Erin took the newest learners. Miles (right) got Lai Nu, among others. I got the boy with the orange spiky hair (left) and Konnai, the one with the best yellow thanaka design on his cheeks.

I guess I can never go on vacation from teaching, but for this lesson the pleasure was all mine. Their questions exceeded the ability of their Japanese peers. I was asked to pronounce “vocabulary,” spell “photogenic,” and exemplify the meaning of “vague.”

Under the watchful eye of Buddha, I grew attached to these young minds. They had an economic necessity to learn English as a ticket to a tourism job to escape poverty that ensnares most of this country’s 52 million people. Their dreams were intertwined with the language I take for granted.

Suddenly my experiences in Japan felt cheap. It was here that students needed (and wanted) help – not to pass entrance exams, but to make a life better than their parents could give them. I thought about what awaited me back in Japan: a new position in a private school full of uniformed children in a charmless suburb of a concrete capital. Sure Japanese kids are cute, but the exotic setting made teaching young Buddhists more alluring.

It was 10:00 p.m. Dust from the ancient cities still coated my face. Both camera batteries were drained. We hadn’t had eaten since a $3 restaurant lunch (the total for three people), but I could have gone all night. However, out of concern for worried mothers, we ended the lesson with high-fives.

These energetic and appreciative Burmese boys and girls made their Japanese counterparts seem like cookie-cutter clones. The Japanese had no character, no thanaka. No longyis tied around their waists. One was tied around mine (a $5 acquisition in Amarapura), which the kids retied correctly while hugging me tight (but not grabbing what lay beneath like in Japan).

This was an incredible and incredibly local experience. The glow inside me peaked as I climbed into the bed of a pickup truck taxi to our hotel. The kids surrounded the truck, and I handed out hugs and high-fives. I guardedly promised to return after my upcoming contract was complete. A headlight then caught my attention. The orange spiky haired boy was revving up his motorbike while friends piled on. We exchanged one last smirk, for this year at least.

View my top 125 pictures of Myanmar here.

Posted by

ジェフリー

at

8:00 AM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: international travel

Monday, July 17, 2006

Going Up?

I had three weeks in between jobs. The day after my last at Kanokita, I was on a plane to Myanmar. There was something excitingly controversial about visiting a country where the Lonely Planet cover included parenthesis around the country’s name (Burma).

I had three weeks in between jobs. The day after my last at Kanokita, I was on a plane to Myanmar. There was something excitingly controversial about visiting a country where the Lonely Planet cover included parenthesis around the country’s name (Burma).

The contrast between industrialized Japan and a land using World War II-era buses was startling. Traveling by train provided an even bigger contrast. The following is an entry lifted outof my journal:

3/20/06 There was nothing special or express about the “15 Up Special Express” going north (or up) from Yangon to Mandalay. Wide, padded upperclass seats offered ample legroom, but the carriages were vintage Chinese jobs. The seatback reclined 120 degrees, but the bottom cushion slipped forward, creating an abyss for my ass.

There was nothing special or express about the “15 Up Special Express” going north (or up) from Yangon to Mandalay. Wide, padded upperclass seats offered ample legroom, but the carriages were vintage Chinese jobs. The seatback reclined 120 degrees, but the bottom cushion slipped forward, creating an abyss for my ass.

I was surprised to be the only foreigner. Ordinary class (wooden upright seats, no electricity) was for locals, some of whom paid extra for the “comforts” I was “enjoying” for $35. Even my air pillow met its match on Myanmar Railways.

While the guidebook didn’t mention anything about air-con, it didn’t mention anything to the contrary. Ceiling fans sat motionless while the sun baked the train in the station. Two men in forest green uniforms began smoking.

Like Japan, departure at 18:00 was on time. Apparently this called for a thunderous send-off with Burmese rock music blaring from the speakers (that worked all too well). The beats outpaced the train’s speed. So did a boy on a bicycle. Is this why the 650 km (400 miles) trip took 14 hours? The rock music was a distraction from the heat, but auditory discomfort lasted until the music switched to more poppy beats to which the rattling train grooved.  Families sat on weedy tracks, some with a teapot and food while train-chaser kids jumped from tie to tie. Yangon’s grimy outskirts gave way to thatched huts and concrete stupas. The country air smelled sweet like a campfire. As the sun set over the flat plains of the Bago Division, the sky turned the color of the pink-robed female monks sitting behind me. Dusty breezes (now cooler) mixed with Vegas brand tobacco fumes across the aisle.

Families sat on weedy tracks, some with a teapot and food while train-chaser kids jumped from tie to tie. Yangon’s grimy outskirts gave way to thatched huts and concrete stupas. The country air smelled sweet like a campfire. As the sun set over the flat plains of the Bago Division, the sky turned the color of the pink-robed female monks sitting behind me. Dusty breezes (now cooler) mixed with Vegas brand tobacco fumes across the aisle.

To my pleasant surprise, at 18:30 bare bulbs flickered to life. Locals continued reading The Flower News while I journaled, now in the company of insects who detected that I was the only foreigner on board. At first, many of the bugs that blew my way were small and dead. Further north, they increased in size and vitality.

I bought only one bottle of water so that I could avoid using the restroom. I thought I could handle 14 hours, but the narrow gauge tracks provided stagecoach comfort. A few bounces nearly threw me out of my seat.

Of course, this jostled my bladder, too. With the train rattling, peeing into the open-hole pit was a physical challenge. The door jammed closed, leading to momentary panic of being trapped for the remainder of the rough ride. At first, I enjoyed the bounce like a cheap amusement park ride. However, the hours dragged on, and I found myself the only one awake after midnight. I guess everyone else got used to it. Some slept on mats under the seats or in between cars, including in front of the restroom. The lights remained on, so to pass the time I began a log:

At first, I enjoyed the bounce like a cheap amusement park ride. However, the hours dragged on, and I found myself the only one awake after midnight. I guess everyone else got used to it. Some slept on mats under the seats or in between cars, including in front of the restroom. The lights remained on, so to pass the time I began a log:

00:15 We’re stopped. Noises outside, but no lights. Men are near the undercarriage of my car. A kerosene torch reveals their shadowy figures like a Rembrandt painting. They have longs sticks, or were they guns?

01:15 Pyinmana. This is the remote interior city where the dictatorship is moving the capital from Yangon to better consolidate its grip. Darkened faces are waiting in dark places. People are sleeping wherever there’s room – under benches on the platform or in piles of dirt to be used for construction.

“Hey lama, hey gobimon, wabey!” a woman repeats while walking up and down the tracks balancing a basket or water jug on her head.

A barbed wire fence separates me from the kids clustered outside my window. A pig the size of some cars here feeds on garbage by the tracks. The shadows and unfamiliar shapes make my hairs stand on edge.

01:59 Do you really have to smoke that cigarette now?

03:01 Snack time! Caramel and peanut candy and Cowhead Chocobiscuits.

04:07 Landing rights denied to huge beetle thing. Thwà-zàn! (Go away!).

05:05 We have arrived in Thazi (English announcement) 10 minutes early. Hawkers board trying to sell moist face towels. Bags of something are piled high on the platform. My throat hurts – from the air? From the insects? It’s cooler out. Some people in the train are sleeping with blankets.

05:11 Snack time! These Cowheads are addictive.

05:35 Third bathroom break. It’s like peeing off the back of a galloping horse.

06:11 Here comes the sun.

06:34 Here comes the music. Again.

07:56 Arrival in Mandalay, the country’s second largest city, four minutes ahead of schedule, which, come to think of it, beats trains in Japan.

Key statistics:

13.9 hours of travel time

10 Cowhead biscuits consumed

5 big, itchy bug bites

2-3 hours of interrupted sleep

0 more times I’ll take the train over a plane to Mandalay.

Posted by

ジェフリー

at

7:30 AM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: international travel, transportation

Monday, July 10, 2006

Reflections

It seems like a long time since I first stepped into a classroom. A year has come and gone, and in its course yielded unanticipated lessons. I’ve chronicled the day-to-day mischief and chaos I’ve witnessed, but after the final bell, what has this teacher learned?

It seems like a long time since I first stepped into a classroom. A year has come and gone, and in its course yielded unanticipated lessons. I’ve chronicled the day-to-day mischief and chaos I’ve witnessed, but after the final bell, what has this teacher learned?

In a world of poverty and politics, natural disasters and nuclear weapons, I’ve come to value innocent students as an outlet for juvenile jokes and mutual companionship. School immersed me in the simplicity of malleable minds free of adult worries and real-world problems.  Junior high in Japan was a triumphant return to a time in America that I’ve tried to black out; I never even bought a yearbook then. This job gave me an opportunity to make up for one of those three years of misery. More than 10 years later and on another continent, I finally became one of the cool kids, just disguised as a teacher in Pumas.

Junior high in Japan was a triumphant return to a time in America that I’ve tried to black out; I never even bought a yearbook then. This job gave me an opportunity to make up for one of those three years of misery. More than 10 years later and on another continent, I finally became one of the cool kids, just disguised as a teacher in Pumas.

Friendship was superficial, but I wasn’t expecting to forge life-long connections with kids half my age. We bonded for the moment, and it was the moment that counted. Our lives intersected fleetingly, but these students touched me (spiritually, but certainly also physically) in ways their American peers could not. They patched a void of camaraderie in a confusing culture where I maintain shallow roots. Japan – with its traditions, etiquette, food, and language – is arguably the most complex country on earth. To even begin to grasp the intricacy of this society is a challenge that takes months of close observation. Businessmen and tourists don’t stay long enough to gain a sense of true Japan.

They patched a void of camaraderie in a confusing culture where I maintain shallow roots. Japan – with its traditions, etiquette, food, and language – is arguably the most complex country on earth. To even begin to grasp the intricacy of this society is a challenge that takes months of close observation. Businessmen and tourists don’t stay long enough to gain a sense of true Japan.

I came face-to-face with raw culture in a working class ward not in any guidebook: I participated in daily life at public school. In return, students got up close (and often too personal) with a foreigner otherwise inaccessible at their sheltered age. We symbiotically brightened the boredom of the curriculum through high-fives, immature jokes, and recess sports. The universality of shared company overcame the awkward exchange of languages. When crossing cultures, baby steps in communication feel like a big connection. With wide eyes and curling corners of mouths, they signaled that our company was more than just shared – it was appreciated. Even cherished. I felt like big brother, and wanted to hang out with students after school and pass around bags of dried squid and melon flavored chips while fighting over PlayStation2 controllers.

With wide eyes and curling corners of mouths, they signaled that our company was more than just shared – it was appreciated. Even cherished. I felt like big brother, and wanted to hang out with students after school and pass around bags of dried squid and melon flavored chips while fighting over PlayStation2 controllers.

After growing up, I never thought much about kids, especially not working with them. I became a teacher in Japan because it’s the easiest path to a work permit. I never expected to become attached to those half my age and of a startlingly different ethnicity. They taught me more about life and about myself than I taught them grammar. We grew together, but on different wavelengths. Through teaching I came to understand the power of a personal touch. Few jobs can influence the direction of someone else’s life. Part educator and part entertainer, I planted seeds of English and Americana in spongy minds. I know that more than a few will mature into interpreters, translators, even English teachers. I never realized this power from my days on the receiving side of the lectern.

Through teaching I came to understand the power of a personal touch. Few jobs can influence the direction of someone else’s life. Part educator and part entertainer, I planted seeds of English and Americana in spongy minds. I know that more than a few will mature into interpreters, translators, even English teachers. I never realized this power from my days on the receiving side of the lectern.

A Douyoto School girl chose this to say in a composition about “one important thing:”

Though I’m doing bad and good things…varied things, I’m having a good time at school. I think I can enjoy school life by grace of friends. There are disgusting things in my school life. But my friend gives me spirits a lift when I feel down.

The school which has many friends is pleasant place!! I have a dream. One day, all students will go to school. To be a part of these young lives for however brief, the memory – on both sides – will persist. None of them (thank god) are reading this, but if they could, I’d want to look them in the eye and with a slight bow of my head say “thank you.” You were my reason for staying in Japan – hundreds of reasons, in fact. Each one similar but slightly individual.

To be a part of these young lives for however brief, the memory – on both sides – will persist. None of them (thank god) are reading this, but if they could, I’d want to look them in the eye and with a slight bow of my head say “thank you.” You were my reason for staying in Japan – hundreds of reasons, in fact. Each one similar but slightly individual.

The end is just the beginning. Stay tuned for a whole new season of students.

The New Batch drama premiers this September.