The odds were 5 in 32 million. Maybe I should buy Mini Lotto takarakuji tickets more often. Sadly, I won’t be calling into work “rich” anytime soon. This wasn’t about scratch-off luck.

Middle school students look alike in their uniformed uniformity, but something made me look twice at one girl walking towards me on the sidewalk. But my iPod was acting up again, so I glanced down to fiddle with it.

“Jefu?” Did someone just call my name? I looked up in panic. How does she know my name? She must be one of my students, but quick – from which school? She’s with four others. Hello, Omiyada 8th graders! Thank goodness for school-issued book bags. However, we were in the sumo district, not near their school where I had just finished teaching for the day. They fumbled for English, and I for Japanese. We could only keep shaking our heads and uttering “ehhh” as the Japanese do when words fail.

They fumbled for English, and I for Japanese. We could only keep shaking our heads and uttering “ehhh” as the Japanese do when words fail.

“What are you doing here?” they pieced together.

“I live here! A 25-minute walk,” I said, pointing south. On my way home from Omiyada, I stopped to research offbeat museums in this area for an upcoming magazine feature.

“Now, what are you doing here, and why the hell weren’t you in school today?” Turns out they, too, were on the museum circuit, but for a school project. The entire 8th grade was turned loose on the town, unchaperoned and armed with notebooks and disposable cameras to document their findings. Had it been Kanokita School, Tokyo would have been on orange alert.

Turns out they, too, were on the museum circuit, but for a school project. The entire 8th grade was turned loose on the town, unchaperoned and armed with notebooks and disposable cameras to document their findings. Had it been Kanokita School, Tokyo would have been on orange alert.

This group had just come from the one-room fireworks museum, which was exactly where I was heading. “It closes at 4:00, doesn’t it?” They looked rather astonished, so I pulled out an itinerary with museums names printed in kanji to illustrate my own assignment. I considered buying them a round of burgers at Macku if they did some of my legwork. I pointed them in the direction of the tabi museum where I had spent a whole 30 seconds. Tabi are split-toe socks worn with kimonos. We laughed at the absurdity of such a place, bested only by the Shinkansen (bullet train) brake museum and the safe and key museum nearby.

I pointed them in the direction of the tabi museum where I had spent a whole 30 seconds. Tabi are split-toe socks worn with kimonos. We laughed at the absurdity of such a place, bested only by the Shinkansen (bullet train) brake museum and the safe and key museum nearby.

Tuesday, January 31, 2006

Chance Encounter

Posted by

ジェフリー

at

9:30 AM

2

comments

![]()

Labels: Omiyada

Thursday, January 26, 2006

The Long Goodbye

It started with Douyoto’s 7th grade section 1-1, and it’s going to last until mid-March. Not long after I finally finished introducing hobbies, height and number of family members to the 50 classes in four junior high schools, it’s time to start saying good-bye. Forever. I beefed up my student photo alum with requests for class pictures. “I’ll never forget you, class 1-1,” I waxed in Japanese as students shuffled up to the board — some more willingly than others —while careful not to intermingle genders. Some paused for a moment, processing my profound words spoken in their native tongue. One boy felt moved enough to respond: “But I’ll forget you!” Thanks, kid.

I beefed up my student photo alum with requests for class pictures. “I’ll never forget you, class 1-1,” I waxed in Japanese as students shuffled up to the board — some more willingly than others —while careful not to intermingle genders. Some paused for a moment, processing my profound words spoken in their native tongue. One boy felt moved enough to respond: “But I’ll forget you!” Thanks, kid.

While hundreds of faces inevitably blur together, a few stand out. I’ll miss the two sumo. Only eight schools citywide have sumo teams, and Nebiko – a barrel of flesh – placed second in the Tokyo junior high tournament.

In the same class is his shorter sidekick, also with a shaved head and no neck, sort of like a soccer ball, but with ears shaped like satellite dishes. Neither can speak much English, and from what I saw of their compositions, their Japanese ain’t good either (mostly written in hiragana while other students used more complex kanji characters). Gambatte, guys.

I’ll also miss the 7th grader who, shaped more like a linebacker than a sumo, left red marks on my hand every time we high-fived. I won’t forget the patient pronunciation of another 7th grader with whom I spent hours after school reciting John Lennon’s “Imagine” for her eventual speech content triumph.  For the 9th graders soon to enlist in high school, I exploited the occasion of our last class to indoctrinate young minds with Jefu’s four tips for a good life:

For the 9th graders soon to enlist in high school, I exploited the occasion of our last class to indoctrinate young minds with Jefu’s four tips for a good life:

#4 Follow your heart, desires, dreams, passions, whatever. I think I used the phrase, “Be all that you can be,” but left out the toll free U.S. Army recruitment number. Just don’t become joyless dark-suited sacks of salarymen. Japan already has more than its fair share.

#3 Come visit me in New York. Not now, but once you master enunciating “r”s and “l”s as different sounds.

#2 Keep practicing your English. It might land you a better job. You are very young, and can eventually become fluent like me (laughs of disagreement).

#1 Do. Not. Smoke. (Pounding heart and lungs) Ever. I know your grandmother and father’s mistress do, but I don’t care if you never practice your English again so long as you aren’t plunking change into a cigarette vending machine glowing from every street corner.

“Yayaaa,” one boy with spiky hair moaned while squirming in his seat. “I inherited a strong body from my mother, so I will be okay.” The Japanese English teacher laughed and translated, whereupon I shook my head. Still, I remain hopeful that when such decision-making times come in the future, that they’ll remember the cool, tobacco-free New Yorker who made English class slightly less boring than usual.

This influential power of teachers became apparent near the end of a 7th grade class. A nondescript boy approached me with a pad of Post-Its. He wanted me to sign the first two. My eyes followed him back to his seat. How would he tarnish sensei’s name?

Suspicion dissolved into disbelief as I watched him open a glue stick and carefully adhere my signature to the cover of his notebook. A lump formed in my throat. It was that moment that validated my entire Japanese experience.

Posted by

ジェフリー

at

9:00 AM

1 comments

![]()

Labels: Douyoto

Monday, January 23, 2006

Long Time, No See

“Miyukiiii, you’re late!” shouted a teacher from his sidewalk post.

The staff of Douyoto School acts like protective parents stationed on street corners around the school looking out for stragglers. This is a small school – only 280 students, and thus has a family atmosphere. They almost lost one member before my eyes. Had the same teacher not blocked Miyuki’s intended sprint through the crosswalk, he would have had an unfortunate encounter with a minivan.

It was a bittersweet week. I hadn’t taught at my favorite school since Halloween, but January’s reunion would be short-lived. It was my final scheduled appearance. The 7th graders seemed to have forgotten my name because some insisted on calling me Johnny or Bobby. I think they’ve been watching too much TV again. Nevertheless, they welcomed me back with open arms and a few questions, like “how do you say ‘anus’ in English?” and “was that you on TV?” I hope the two weren’t related. I quizzed them with listening comprehension passages about Thanksgiving and Hanukkkah. Unlike at Kanokita School, where only the walls pay attention, Douyoto students volunteer to recite model textbook readings. English, while not as popular as gym, is at least favored over math and art. In a school survey, 61% rated English as either their favorite subject or one they like.

I quizzed them with listening comprehension passages about Thanksgiving and Hanukkkah. Unlike at Kanokita School, where only the walls pay attention, Douyoto students volunteer to recite model textbook readings. English, while not as popular as gym, is at least favored over math and art. In a school survey, 61% rated English as either their favorite subject or one they like.

This, after all, is the school where I coached two students to victory in a sweep of the two first prizes at the ward’s English speech contest. Douyoto divided my loyalty by unseating last year’s champion Nubata School, the second favorite of the four I teach at.

As a parting gift, Douyoto 8th and 9th graders gave me a new batch of compositions to correct. The 9th graders, currently mired in jiken jigoku (high school entrance “examination hell”), wrote about their dreams. It was heartening to read their aspirations pieced together in mangled English. Among the future bakers, barbers, clinical psychologists, weather forecasters and nursery school teachers, some didn’t yet have a “future dream.”

Others expressed exactly what they wanted. One boy confessed an urge to “become a temporarily straight adult.” Talk about lost in translation! Two verbalized definitive goals. One, to follow in dad’s footsteps at Japan Rail. The other, to become a conductor on the Seibu line in a 3800 series train, a mechanical diagram of which accompanied his text.

A humble girl had this to say:

I want to be common housewife in the future. Why? First, it is an ideal every morning that send a husband and child out. I am similar afterwards and do terrible housework in various ways and want to finish first. Now I do not like a help of a house very much. Therefore I want to do my best little by little.

I’m setting her up with this boy:

My dream I would like to be happy old man. What’s happy? Happiness might be different for the person. The dream for me is to do to want do it is necessary to do, and doing. It’s my dream!!

Meanwhile, the 8th graders described “their important one thing.” Family, pet cat, soccer ball, baseball glove and Nintendo were common. One girl wrote about having “a considerate heart.”

This capitalistic boy coveted more tangible values:

My important thing is money. A mony can change everything.

Japanese money is yen that has many kinds. The smallest yen is own yen next five, ten, fifty, hundred, 500….A money made all of us happy, and it is life. Comic books enthrall Japanese young and old, apparently even in the afterlife:

Comic books enthrall Japanese young and old, apparently even in the afterlife:

My important thing. It is many comics. It gave me many some thing. For example, knowledge, smiling face, etc…It isn’t miss my life. I like comics. So my coffin in these comics. Because I want to read comics in the other world.

As this blogger well knows, never underestimate the power of the pen:

I have a important thing. It’s a pen. Because it is needed to write. But I often break it. Now I have six pens in my pencase. I often by pen. But it is expensive, isn’t it?

If you say “Yes” you are right.

If you say “No” you are stupit.

Yet even teacher make mistakes. I misspelled cockaroach, cavier and badmitton on the board. I drew an uncomfortable silence after mispronouncing the Japanese word for Thanksgiving (kansha-sai) as kancho-sai. Day of Thanks came out as “enema festival.”

A blooper at recess was just as embarrassing, but more painful. I should have known better than to play a sport I know nothing about while in loafers. I’m not sure how it happened. Maybe I tripped on the soccer ball, or maybe over my own feet, but the next thing I knew I was tumbling. Not just falling down, but a sputtering, flailing dive. Had my palms and right knee not broken the fall, I would have tasted playground dirt.

My stumble drew a chorus of laughs. I casually dusted off my stained trousers, which hid a skinned knee glistening with blood that hadn’t broken the surface. “You’re weak,” one boy shouted in Japanese, adding “and slow, too” while I hobbled after him ready to ring his neck.

I atoned by teaching two 8th grade classes on my own. Technically this is illegal because I am not a certified teacher in Japan.  However, Ms. Kimura had to take her feverish son out of elementary school and to the doctor, leaving me in charge of the lesson plan. I drilled cooperative students on reading passages and vocab before running out the clock with hangman. I told them it was our last class together. They stood up, bowed and gave me a mild round of applause. I high-fived my way out the door for the final time.

However, Ms. Kimura had to take her feverish son out of elementary school and to the doctor, leaving me in charge of the lesson plan. I drilled cooperative students on reading passages and vocab before running out the clock with hangman. I told them it was our last class together. They stood up, bowed and gave me a mild round of applause. I high-fived my way out the door for the final time.

Posted by

ジェフリー

at

8:00 AM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: compositions, Douyoto

Thursday, January 19, 2006

An Eye for IQ

Instead of Aiko’s regular Tuesday night private lesson at my apartment, we took a field trip to a neighborhood sushi restaurant. It’s always packed. The salaryman next to me was watching live soccer on his phone.

Instead of Aiko’s regular Tuesday night private lesson at my apartment, we took a field trip to a neighborhood sushi restaurant. It’s always packed. The salaryman next to me was watching live soccer on his phone.

The place is known for its swimmingly fresh and stunningly cheap seafood. Aiko did all of the ordering, and I did most of the eating – tuna, octopus and squid sashimi and conger eel tempura. The fish was so fresh that for once I didn’t gag at the normally briny stench of sea urchin when it hit my tongue. I nibbled at shredded radish garnishing the sashimi plates.

Just when I didn’t think I had room for any more, soup arrived. Aiko described it as ara shiru, a clear broth with fish bone, head and meat. I cupped my hands around the warm bowl and raised it to my lips. Clean and refreshing.

All that remained was an unidentifiable chunk. Aiko’s bowl was empty. I looked into mine. The meat looked back at me. I couldn’t believe my eyes. I had an epiphany like when your brain unscrambles a Magic Eye optical illusion. From the bottom of my bowl stared a fish eye. Strands of meat clung to the socket, but there was no mistaking the opaque bubble in the middle.

“Are you supposed to eat this?” I cried as quietly as possible.

“Yes, it’s delicious,” Aiko said.

I poked the eye in the eye with a chopstick.

“It’s hard! It’s an eye!”

I can’t remember the last time I got squeamish over food, but the cold look of the eye was jarring. I wanted the waitress to clear my plate, yet out of curiosity I kept poking it as a warm up for the inevitable.

The grey-haired waitress detected my indecision, and told Aiko that boiled sakana no me (fish eye) was good for the skin and intelligence. An eye for IQ.

“Maybe it’s best if you eat it with another food,” Aiko suggested. “Like tofu, if you are scared.” I was scared, but intrigued. Curiosity won, but my taste buds had the final say. My nostrils flared. It was crunchy like plastic. Was it the cornea? Sweet gelatin oozed onto my tongue.

I wanted it out of my mouth and fast, but only had a moist washcloth for a napkin. I pursed my lips, and breathed heavily through my nose. The shredded eyeball sloshed around in my mouth. Teeth cracked on a pachinko ball. Is this what they mean by eyeball? My throat closed. There was nowhere for it to go but back out. I raised the bowl and spat.

Aiko had been watching my contorted facial expressions, which now eased with relief. A swig of beer neutralized the aftertaste. Check, please.

Posted by

ジェフリー

at

9:20 AM

1 comments

![]()

Labels: food

Wednesday, January 18, 2006

Breaching Sashimi Borders

I took a stool at Daruma restaurant, where the scene has been rather quiet the past several visits. I told Masa I was hungry and wanted something “bigger” than my usual meal of kawaebi, the Japanese equivalent of popcorn shrimp. She knew just the thing, and yelled something at the cook, who greased up an already greasy iron pan.

I took a stool at Daruma restaurant, where the scene has been rather quiet the past several visits. I told Masa I was hungry and wanted something “bigger” than my usual meal of kawaebi, the Japanese equivalent of popcorn shrimp. She knew just the thing, and yelled something at the cook, who greased up an already greasy iron pan.

As I awaited the mystery meal, a salaryman on the adjacent stool startled me by striking up a conversation. It was the standard where was I from and where did I live now. He picked at a plate of sliced fish the color of blood. “Do you like kujira?” he asked. I like all types of raw fish, but this looked a little too raw for my taste.

Kitchen hand Nao came over to translate by pictograph. My eyes lit up. This wasn’t just any fish. It was whale. It’s only on the menu of two countries – Japan and Norway – that haven’t banned the practice despite international pressure.

“Some foreigners think it’s rude for Japanese to eat,” the man said, sliding a piece onto my plate. I was surprised to see it served at a hole-in-the-wall like Daruma. Whale is expensive, and its consumption on the decline. It’s now considered a delicacy instead of an entrée at school lunch, which remains a childhood memory one art teacher would rather forget.

The blood-red chunks didn’t look appetizing. Unlike smooth slices of tuna, whale looked more fleshy than fishy. It didn’t dissolve inside my mouth like tuna either. I couldn’t spit it out in front of everyone, and kept chewing until the lump felt masticated enough to wash down with beer.

Squid eyes. Whale. What’s next to cross my lips? Sakana no me. Stay tuned for Fishy Business Part 3.

Posted by

ジェフリー

at

8:10 AM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: food

Monday, January 16, 2006

Squid Eyes

How can you tell if you’ve been in Japan for too long? When hankering for a snack, you bypass the Kit-Kats and Doritos and beeline to a supermarket’s raw fish section.

How can you tell if you’ve been in Japan for too long? When hankering for a snack, you bypass the Kit-Kats and Doritos and beeline to a supermarket’s raw fish section.

I needed an after school pick-me-up, and picked up a container of baby squid. At first I wasn’t sure if its contents could be eaten on the spot. I had never seen squid eyeballs as white beads. Were they supposed to be cooked? My stomach growled. The enclosed packet of mustard was enough to convince me that raw was the way to go.

I lamented the unofficial no eating while walking rule in Japan, but stuffing slimy squid tentacles into my mouth on the way to the train station did seem a little messy. Yet, I couldn’t resist. I looked both ways, and popped the seal. The unexpected crunch of the eyeball almost chipped a tooth. I spit out the rock on the sidewalk, and carefully continued chewing.

My midday snack wasn’t as tasty as it had looked. Once I in the privacy of my apartment, however, the de-eyeballing process was easier. Adding mustard and soy sauce turned raw taste into a tasty treat.  I e-mailed an American friend about crossing new fishy frontiers. She shot back, “That is absolutely DISGUSTING – sounds like you need a care package and quick!!!!!!!”

I e-mailed an American friend about crossing new fishy frontiers. She shot back, “That is absolutely DISGUSTING – sounds like you need a care package and quick!!!!!!!”

Now that you mention it, yes. Everything bagels, pizza without corn and mayo toppings, non-Asian ethnic food and anything else that doesn’t contain dried baby sardines, rice or squid eyeballs would be fine, thanks.

Posted by

ジェフリー

at

8:40 AM

0

comments

![]()

Labels: food

Thursday, January 12, 2006

Taking Swings in Kiba Park

There aren’t too many places at 35°41' North latitude where you can play outdoor tennis in January. Tokyo is one of them. Ironically, in order to avoid the sun’s tanning rays, Japanese women wear more clothing to play tennis in July than in January. In summer’s 137% humidity, I perspire walking to the subway in a t-shirt, but that doesn’t stop women from wearing full sweat suits with long sleeves, mittens and visors inspired by Darth Vader.

There aren’t too many places at 35°41' North latitude where you can play outdoor tennis in January. Tokyo is one of them. Ironically, in order to avoid the sun’s tanning rays, Japanese women wear more clothing to play tennis in July than in January. In summer’s 137% humidity, I perspire walking to the subway in a t-shirt, but that doesn’t stop women from wearing full sweat suits with long sleeves, mittens and visors inspired by Darth Vader.

In cooler conditions and under cloudy skies, I joined the Yamakuma family at well-maintained grass courts in Kiba Park, a half hour walk from my apartment. Kiba means “tree place,” and alludes to the lumber stockyards of the Edo period.  Nowadays, an unsightly concrete bridge accents the park, which attracts a crowd of retired shutterbugs who assemble tripods to document the local wildlife – pampered pooches and plump pigeons. Winter doesn’t enhance this drab park’s appeal, but when in Tokyo one learns to relish open spaces of any kind, even “parks” nestled under overpasses.

Nowadays, an unsightly concrete bridge accents the park, which attracts a crowd of retired shutterbugs who assemble tripods to document the local wildlife – pampered pooches and plump pigeons. Winter doesn’t enhance this drab park’s appeal, but when in Tokyo one learns to relish open spaces of any kind, even “parks” nestled under overpasses.

I tutor Jiro, the Yamakuma’s 7th grade daughter, for an hour on Saturday mornings. She showed up with a racquet, as did adult 6 family friends. We rented two courts, one for the husbands and the other for the wives. I was assigned to the wives’ court.

For two hours we played matches of four games each, rotating partners. While I hadn’t held a racket since an embarrassing defeat at the hands of an American 7th grader while vacationing in Oman a year ago, at least I was able to follow Japanese tennis jargon as we volleyed balls and apologies for hitting them. A typical point consisted of the following dialogue, gasped in staccato female whimpers:  Oh, I’m sorry! Are you ready?

Oh, I’m sorry! Are you ready?

Ahh, excuse me. I’m sorry.

It’s short, excuse me.

It’s okay. Sorry.

Oh, nice serve!

It’s short, so short. I’m sorry.

Almost!

Okay, next. Your turn, please.

Excuse me, please have a ball. Thank you.

Oh, thank you so much. I’m sorry.

Okay, it’s no trouble. Thank you.

My underhand serve needs work before next week’s qualifying match for Tokyo’s Toray Pan Pacific Open, but I’m set to practice with Nubata’s tennis club after school (also outdoors).

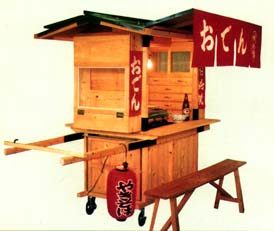

Walking through Kiba Park triggered memories of an earlier visit. I’ve had many bizarre encounters in Tokyo, but this perhaps outranks them all. Back in July, a salaryman at Daruma restaurant took me drinking around the neighborhood. Our last stop was a street cart named yatai. These are portable food vendors, but with fixed sidewalk locations. I pulled up a stool, and the salaryman ordered me a can of Asahi and a bowl of oden, a hodepodge stew of strange root vegetables. Four other locals yammering in Japanese ringed the wooden cart, but became intrigued with the foreign diner.

I pulled up a stool, and the salaryman ordered me a can of Asahi and a bowl of oden, a hodepodge stew of strange root vegetables. Four other locals yammering in Japanese ringed the wooden cart, but became intrigued with the foreign diner.

A woman had a son my age, but after 45 minutes the salaryman left me on my own for translations. A man of about 50 with a shaved head and athletic build bought me another can and then a round of sake, which unfortunately were not elixirs to clarify his speech. Even the salaryman had trouble comprehending his thick Japanese with a heavy accent of intoxication.

The yatai chef was calling it a night, and my new friend – missing a bottom front tooth – smiled at me to follow him to the corner. Before the light changed to cross, he hailed us a cab. Climbing in sent shockwaves of uncertainty in this order: (1) cabs are an unaffordable luxury, (2) how was I going to get home from where we were going, (3) where were we going and (4) who the hell was this guy? I began noting landmarks to help me retrace the route for the long walk home. Two right turns and a trapezoidal bridge later, the cab stopped. There was a convenience store and park. We went into the conbini first.

I began noting landmarks to help me retrace the route for the long walk home. Two right turns and a trapezoidal bridge later, the cab stopped. There was a convenience store and park. We went into the conbini first.

“Hanabi!” I pointed at the fireworks hanging from a rack by the door. I thought I had seen it all, the young clerk was thinking to himself as he eyed the drunken odd couple buying fireworks at half past midnight on a weekday.

The man, who paid for the cab and fireworks, hadn’t stopped talking through either. I was absolutely clueless as to what he was saying as we walked to a grassy field illuminated by street lamps.

I gazed up at the night sky. The next thing I knew, I was seeing stars. I had been knocked off my feet with some martial arts maneuver. And now I was angry. I charged back to return the favor, but bounced off; he was built like an ox.

I can’t remember how long this midnight melee lasted, but it ended as abruptly as it began. He started walking home. I ran after him to hand him the fireworks we’d abandoned. A banzai scream broke the silence as he punted the package into a stand of trees.

I woke up at noon wondering if it was all but a dream. Grass stains on my track pants told otherwise.

Posted by

ジェフリー

at

10:05 AM

0

comments

![]()

Tuesday, January 10, 2006

Shock ‘n’ Defrock

It was judgment day at Nubata School. What do you want to be in the future? That was the lesson planned for 8th graders. I was to ask each student his or her aspirations just as soon as the teacher passed back last semester’s English test. The Japanese school year is divided into three, and each marking period has one or two tests per subject.

The students looked nervous, and given their scores I would have been, too. Mr. Nakamura called out names, and students lined up with tortured looks to receive their academic fate. “Is this test out of 100?” I whispered. Mr. Nakamura chuckled with embarrassment. I was seeing red inked numbers in the teens.

“Ayyy sensei,” one girl cried, quickly folding her paper. Another grabbed her pigtails in frustration. One student aced the exam. It wasn’t the guy shredding the paper under his desk. It seemed that the quietest students either understood class very well (85% and above) or were hopelessly clueless (25% and below). “That’s pathetic,” I said in Japanese, patting the shoulder of a back row boy who fell three points shy of breaking double digits. I hope there’s a curve.

I began the lesson with a row of girls, who professed desires to become rich girl, pretty girl, rock star girl or a great human. I then moved to the boys by the window because they have the shortest attention spans. One wanted to become “a wind,” which seemed to make sense to him in his little world of anime artfully drawn in his notebook’s margins.  The third boy back was a little rascal with a shaved head and mischievous eyes known as Saito. “I want to be a priest,” he said laughing and waiting for me to react. I shrugged off his insincerity, and queried the boy behind him.

The third boy back was a little rascal with a shaved head and mischievous eyes known as Saito. “I want to be a priest,” he said laughing and waiting for me to react. I shrugged off his insincerity, and queried the boy behind him.

Saito apparently was serious because he suddenly grabbed my ass. Not just a friendly pat on the butt, but a full-on, crowded train chikan grope. I wheeled around in disbelief to see Saito grinning with his hand still outstretched. He repeated his desire to join the clergy. “That won’t be a problem,” I assured him. “I’m sure the priesthood will just love you.”

Stern warnings only embolden Saito, who unfortunately continues to fumble around for out-of-bounds places. It could be worse. I’ve yet to be a kancho victim. This word is Japanese for enema, and is a popular ruse with elementary school boys who, hands clasped like a gun, sneak up and jam outstretched index fingers into a buddy’s rectum.

Somehow, I just don’t see this catching on with American kids, but the time-honored tradition is alive and unwell in Japan. T-shirts available. Arcade games (gulp) available. Sick stuff? Hardly the tip (ahem) of the Japanese iceberg.

Saito’s friend Kenichi, who has a sharp wit and perhaps the best English in the class, had a flattering response. “I want to be a Jeff-sensei in America,” he said of his desire to teach Japanese to Americans. I clutched my heart. Had I finally broken through to a student? Of course not. After class, Ken said he was just kidding. He wanted to be a priest. I dodged his hand just in time.

Posted by

ジェフリー

at

8:30 AM

0

comments

![]()

Friday, January 06, 2006

Private Dancers

It was a “one-derful” day. In the teachers’ room, my chin rested on a notepad where I was jotting down thoughts. I was scheduled to teach just one class, and that was three hours ago during first period. I wait until after the subsidized school lunch to ask to be excused for the day.

Two girls entered the room with a soft “shitsuri shimasu,” which is customarily said upon a entering a room to apologize for the disturbance created. Whatever teacher they were looking for wasn’t here – I was alone. When they didn’t leave, I looked back up – they were looking for me!

I asked them where we were going. A lanky girl said “the sports dome.” Intrigued, I followed. We headed to a room above the gymnasium where once I did taiko drumming with the “handicapped students.”

Girls were milling around in their gym clothes awaiting Haruko’s instructions. Male students affectionately call this gym teacher “short, fat woman” in English. She seems to embrace the appropriate description.  Haruko’s class was practicing Japanese folk dances to be exhibited at their upcoming school festival. Each student grasped a yellow and white sensu (Japanese fan) and shakujo (stick rattles with metal bells). The girls, some beaming behind their fan-shielded giggles at performing for a visitor, took their positions.

Haruko’s class was practicing Japanese folk dances to be exhibited at their upcoming school festival. Each student grasped a yellow and white sensu (Japanese fan) and shakujo (stick rattles with metal bells). The girls, some beaming behind their fan-shielded giggles at performing for a visitor, took their positions.

Haruko popped in a crackling cassette. The girls swayed to the traditional rhythms. The fisherman’s dance looked like a reenactment of an epic tug-o-war. And if you’ve seen the size of the torpedoes auctioned in Tskuji fish market, you’d understand why.

The girls watched my reaction as they twirled. They were no longer dancing for Haruko; they were dancing for me. The choreography, music and intimate setting felt like the real Japan. Sure, Japanese festivals are impressive staged events, but this uncostumed, raw demo in a middle school gymnasium felt more visceral.

Despite a few dropped fans and miscalculated tugs that sent some toppling over, the girls executed well. One dance was a school tradition performed since 1983.

“Shall we dance,” a girl asked me near the end of class, quoting the recent movie based on a Japanese film. Others called for me to join, but I sat contently watching the young experts.

Posted by

ジェフリー

at

9:00 AM

2

comments

![]()

Labels: Omiyada

Tuesday, January 03, 2006

Gongs At Midnight

Fifty minutes to midnight, I was in my apartment with a sixer of Sapporo munching on day-old sushi and gizzard skewers. The television was on. I was exactly where I wanted to be.

Fifty minutes to midnight, I was in my apartment with a sixer of Sapporo munching on day-old sushi and gizzard skewers. The television was on. I was exactly where I wanted to be.

The New Year’s Eve tradition of kohaku uta gassen was in full swing. J-pop stars were pitted in a battle of the sexes while kimono-clad enka singers waxed about unlucky love to sway the older demographic. Gorie, the transvestite comedian, sided with the girls’ team. While the parade of talent featured a few too many feathered boas for my taste, not so for the average Japanese household, 50% of whom tune into the program (down from 80% in the 60s-70s).

Unlike in the West, New Year’s in Japan is steeped in tradition more meaningful than champagne, Dick Clark and Times Square. The holiday is similar to Thanksgiving in that it’s the one time families get together. Bamboo and pine ornaments adorn entrances, soba noodles symbolizing longevity are slurped whole and bizarre seasonal foods crowd supermarket aisles.

Also unlike in the West, I was having trouble getting myself invited to a year-end celebration. Time was running out, and so were the contacts in my phone book.

Hidemi was with her family in Mie prefecture. Basketball buddy Takahiro was down the street, but also with his parents. Sweet Kaori was texting me to arrange a follow up to her trial lesson in June. Nao (male) was going to Yokohama for an event staff party. Nao (female) wasn’t returning messages. And I wasn’t returning Fumiko’s.

Yoichi was having a party in his apato, but then suddenly changed plans for Chiba. Michelle and Nobu were in New York. Lawrence was in France. Hicca, of restaurant and radio fame, was in the hospital with a brain tumor. I almost thought about texting Satoshi. Almost.

So, like most other days here, I spent omisoka alone, but not lonely. Another tradition is to visit a shrine at midnight, or sometime during the three-day holiday. About 70% of Japanese make a pilgrimage for ceremonial rather than religious reasons. More than three million descend upon Tokyo’s Meiji Shrine, which is about the number of salarymen swarming into my Otemachi-bound subway car on non-holidays.  Luckily, my neighborhood is home to Tomioka Hachimangu Shrine, perhaps one of the five most important in Tokyo. At 30 minutes to midnight, I set out to rendezvous with the god of war. Just Hachiman and I would ring in the New Year together. Little did I expect such a crowd to vie for his attention.

Luckily, my neighborhood is home to Tomioka Hachimangu Shrine, perhaps one of the five most important in Tokyo. At 30 minutes to midnight, I set out to rendezvous with the god of war. Just Hachiman and I would ring in the New Year together. Little did I expect such a crowd to vie for his attention. The shrine was packed with people waiting to make a wish. Food stalls cooked up tempting treats in a haze of scented smoke. Never mind champagne, it was tako-yaki time (fried octopus-filled golf balls, right).

The shrine was packed with people waiting to make a wish. Food stalls cooked up tempting treats in a haze of scented smoke. Never mind champagne, it was tako-yaki time (fried octopus-filled golf balls, right).

I exchanged greetings with two basketball acquaintances who spotted me while awaiting their fortune slips. Not wishing to wait in line for a custom I didn’t understand, I played roving photographer. I nudged my way up to the front of the shrine just before midnight, and videotaped the clapping crowd as gongs boomed. Some drunken guys hoisted one of their own, and bounced him as if he had just scored the winning goal.

The best part about the New Year, however, isn’t the anti-climatic countdown. It’s wishing random people well. This was made more satisfying in Japan where I was a foreigner unexpectedly equipped with the right phrase, and – after five Sapporos – emboldened to startle strangers.

Among those I bestowed New Year’s wishes upon were the supermarket checkout clerk (to purchase said Sapporo), the muffin girl in the silly hat working the bakery aisle, grandma Yoko the Chiyoda Sushi lady where I order out three times a week, a gang of high school troublemakers sitting on a park fence and a couple walking a dog down a quiet side street.

I spotted another young couple. “Sumimasen, shin nen no hofu wa nan desuka?” (What’s your New Year’s resolution?). Waiting for the walk signal, they were trapped. In typical Japanese style, the woman repeated my question. She then shot her boyfriend/husband the look. Traffic stopped. He laughed to end the conversation. The response needed no verbalization: more sex in ’06.

I continued to indulge in Japanese tradition on New Year’s Day, as I made a McTeriyaki burger my first meal of 2006, and watched the 85th Emperor’s Cup soccer match in bed (the red team won).

While I received no fortune at the shrine, I got an e-mail from Atami, a Douyoto 9th grader. His message was one we can all embrace: “2006’s ambition is ‘Don't forget progress spirit always.’” Amen, little guy. It’s going to be a good year here in Tokyo. Akemashite omedetou gozimasu to you, too.

Posted by

ジェフリー

at

8:30 AM

2

comments

![]()