Once in Mandalay, I reunited with Erin & Miles, fellow American traveling buddies I had met in Yangon. They had taken the overnight bus, and after hearing stories of a flat tire, midnight military checkpoints, and sub-zero degree air-con, I concluded that the train was the lesser of two evils. For sunset, we headed up Mandalay Hill. During our barefoot half-an-hour climb, we encountered a group of “students” ages 13 to 18. We had heard this story before. I thought they were hustlers, but was quickly proved wrong. One boy even bought me a bracelet. Others clutched a printout with questions to ask tourists to practice their English. They seemed thrilled to talk to Americans. Not many native English speakers care to visit a military dictatorship with a history of human rights violations.

For sunset, we headed up Mandalay Hill. During our barefoot half-an-hour climb, we encountered a group of “students” ages 13 to 18. We had heard this story before. I thought they were hustlers, but was quickly proved wrong. One boy even bought me a bracelet. Others clutched a printout with questions to ask tourists to practice their English. They seemed thrilled to talk to Americans. Not many native English speakers care to visit a military dictatorship with a history of human rights violations.

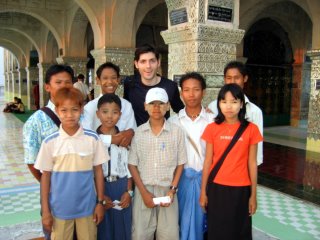

These kids, however, made me glad I broke rank. A 360-degree panorama of the plains greeted us at the top. While other tourists took pictures of the sunset, we Americans gathered the children in a circle and began an impromptu lesson with their undivided attention. I introduced the concept of ‘high-five,’ which we practiced many times.

The walk down was dark. Flickering electricity teased our eyes. At the bottom of the hill we met their 22-year-old teacher. He invited us to class the next evening at a nearby monastery.

* * *

After an ambitious day visiting the ancient cities of Paleik, Inwa, and Amarapura via private taxi, we returned to Mandalay. The sun was done, but teaching duties remained.

The darkened road had no signs, but we knew we had the right place. Headlights illuminated joyous expressions of kids waiting at the monastery’s gate. Apparently, we were the only foreigners who had ever taken up the invitation. The teacher was ecstatic, too, and kept apologizing for the blackout. Although they were scheduled to have power that evening, candles had to be lit. Thirty of us gathered on the floor of a main hall with a huge Buddha statue. I had never envisioned a lesson without a board, much less lights. Suddenly the latter materialized, and Miles took over with charades. It spawned a teaching revolution.

Thirty of us gathered on the floor of a main hall with a huge Buddha statue. I had never envisioned a lesson without a board, much less lights. Suddenly the latter materialized, and Miles took over with charades. It spawned a teaching revolution.

Older students cornered me in the back with questions. When I wrote down words like “amazing,” “gorgeous,” or “guinea pig,” notebooks jostled to copy it down. I couldn’t pay Kanokita kids to do that. Those studying for less than two months had better vocabularies than second-year Japanese students. One surprised me with “nunnery.” I guess vocab lists are different in Buddhist countries (yes, Japan has Buddhists, too, but nothing like Burma).

Learning from the mistakes of the Japanese school system,  I decided to divide the group based on ability. Miles, Erin, and I each took a group. Erin took the newest learners. Miles (right) got Lai Nu, among others. I got the boy with the orange spiky hair (left) and Konnai, the one with the best yellow thanaka design on his cheeks.

I decided to divide the group based on ability. Miles, Erin, and I each took a group. Erin took the newest learners. Miles (right) got Lai Nu, among others. I got the boy with the orange spiky hair (left) and Konnai, the one with the best yellow thanaka design on his cheeks.

I guess I can never go on vacation from teaching, but for this lesson the pleasure was all mine. Their questions exceeded the ability of their Japanese peers. I was asked to pronounce “vocabulary,” spell “photogenic,” and exemplify the meaning of “vague.”

Under the watchful eye of Buddha, I grew attached to these young minds. They had an economic necessity to learn English as a ticket to a tourism job to escape poverty that ensnares most of this country’s 52 million people. Their dreams were intertwined with the language I take for granted.

Suddenly my experiences in Japan felt cheap. It was here that students needed (and wanted) help – not to pass entrance exams, but to make a life better than their parents could give them. I thought about what awaited me back in Japan: a new position in a private school full of uniformed children in a charmless suburb of a concrete capital. Sure Japanese kids are cute, but the exotic setting made teaching young Buddhists more alluring.

It was 10:00 p.m. Dust from the ancient cities still coated my face. Both camera batteries were drained. We hadn’t had eaten since a $3 restaurant lunch (the total for three people), but I could have gone all night. However, out of concern for worried mothers, we ended the lesson with high-fives.

These energetic and appreciative Burmese boys and girls made their Japanese counterparts seem like cookie-cutter clones. The Japanese had no character, no thanaka. No longyis tied around their waists. One was tied around mine (a $5 acquisition in Amarapura), which the kids retied correctly while hugging me tight (but not grabbing what lay beneath like in Japan).

This was an incredible and incredibly local experience. The glow inside me peaked as I climbed into the bed of a pickup truck taxi to our hotel. The kids surrounded the truck, and I handed out hugs and high-fives. I guardedly promised to return after my upcoming contract was complete. A headlight then caught my attention. The orange spiky haired boy was revving up his motorbike while friends piled on. We exchanged one last smirk, for this year at least.

View my top 125 pictures of Myanmar here.

Sunday, July 23, 2006

Mandalay on My Mind

Posted by

ジェフリー

at

8:00 AM

![]()

Labels: international travel

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment